At least once a year I visit two small museums that demarcate the extents of my East Coast travels: the Norton in West Palm Beach, Florida, and the Farnsworth in Rockland, Maine. My qualms with the latter, which were all but mitigated by the cheerful ministrations of museum staff on this most recent trip, have to do with the institution’s uncritical promotion of all things Wyeth. More on that later. For the moment it’s sufficient to note that the Farnsworth offers rewards that larger museums would deem esoteric; an exhibition of Edwin Austin Abbey’s Shakespearean subjects a few years ago was a spot-on reconsideration of one of our great and largely forgotten draftsmen. The museum has a solid holding of American and especially Maine art, some of which supplements its current exhibitions. There’s a micro show highlighting selections from the permanent collection, as well as a couple featuring work by and about women.

These are diversions from the main events, one of which makes a case for the importance of Marguerite Zorach as an early proponent of modernism (coincidentally, Zorach was featured prominently in an exhibition on female modernists last year at the Norton). Zorach’s painting, with its echoes of Max Weber and Charles Demuth, was in the early twentieth century vanguard. Her student painting was vigorously Fauvist. When they met in 1912, William Zorach, her future husband, looked at her work with puzzlement; “I just couldn’t understand why such a nice girl would paint such wild pictures.” The Zorachs kept homes in Maine and New York, and William taught sculpture for decades at the League. They worked closely together, but per the sexism of the era, William was viewed as the dominant artist. The current show, curated by Jane Bianco, is a belated corrective.

Marguerite soon turned to cubism, a transition that reined in both her palette and her emotional expressiveness. One of her best paintings is the Art Deco Nude of 1922, the figure’s fertile contours belied by a pose of resolute inaccessibility—she simultaneously displays a sumptuous physicality while contorting her body in an effort of self-concealment. The inevitable comparison to Matisse misses the tortured ambiguity of the gesture, a stylization that’s closer to that of the droll American cartoonist Ralph Barton. Equally powerful is Two Nudes, painted the same year and in keeping with the Adam and Eve theme that Zorach often revisited, though here the figures are depicted back-to-back, the man half-hidden and of secondary importance to the classical female nude. After a hiatus to raise her children, Zorach returned to painting in the 1930s, producing WPA-style murals like Land and Development of New England, a work every bit as exciting as its title, and whose main figures—notwithstanding the presence of a Bunyanesque gentleman in a flannel shirt—have no apparent substantive connection to the theme. Zorach’s mature canvases possess an interest in fractured pattern, a cubism that was not just a formal contrivance, but which allowed her to juxtapose multiple narrative strands within a single frame. Those strands could be explanatory, as in the background scenery of Land and Development of New England, or opaque to the point of indecipherability, as in Shore Leave. The sensibility is both feminine and feminist, evidence of the art form Zorach had taken up when not painting.

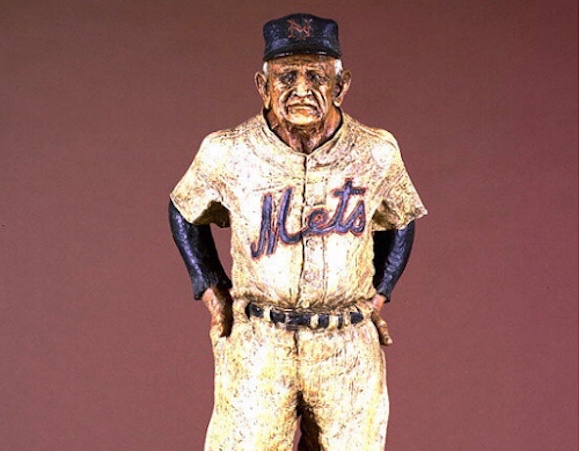

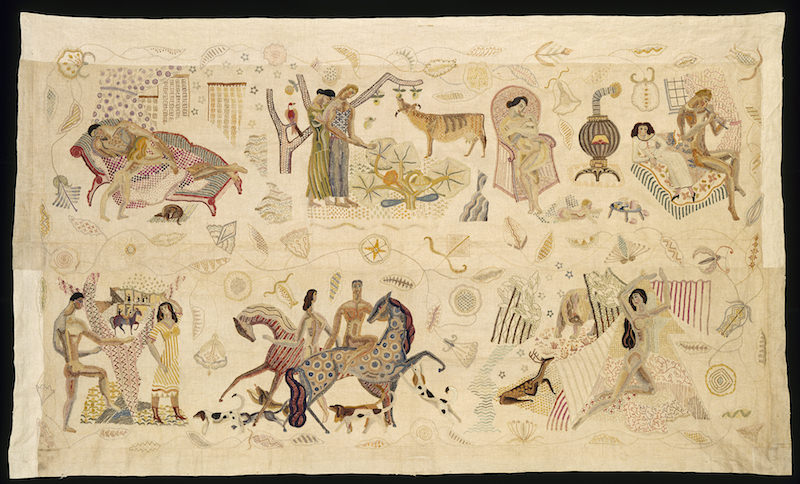

Zorach took pains to identify embroidery as an art form rather than a craft. It was, she said, “an art expression unique with me and not like anything done before.” She called it “wool painting,” but it’s not painting, so I’m inclined to breeze past it. Fortunately I was accompanied by someone with an appreciation for the work, as Zorach practiced it, in all its intricate and varied stitching. The textiles are magnificent. They range from the sublime Embroidered Panel—another piece that summons comparisons to 1920s cartoons—to the dense and ambitious so called Rockefeller Tapestry, a portrait of the family that Zorach created on commission and spent several years finishing; the word “portrait” is used advisedly, for the small figures are each engaged in separate, leisurely pursuits at the Rockefeller’s Maine enclave. Zorach used embroidery to more fully explore multiple narratives than she did in painting. As she explained it, looking after her children clipped the flow of her painting time, but embroidery could be dropped and returned to without the work suffering.

This year would have been Andrew Wyeth’s hundredth birthday, and no museum outside the Brandywine Valley is better suited to joining the celebration than the Farnsworth. Wyeth’s Port Clyde home, formerly that of his father, N. C., sits at the end of the St. George peninsula to which Rockland is gateway. The Farnsworth has collected Andrew’s art since the 1940s, when he was young and not yet famous. The symbiosis has spawned a sizable collection and ever rotating shows devoted to the family’s work, as well as an annex across the street from the museum’s main building bearing the Wyeth name. This is a rather unique acknowledgement of the commodification of the family’s art–up here, Wyeth prints are as ubiquitous as lobster rolls. It’s impossible to visit this part of Maine without recognizing the integral role the art and lore of the Wyeths play in the local economy. All museums depend upon our beneficence, be it in the form of admission fees or super rich donors; the Farnsworth was geographically lucky and prescient in signing on early with arguably the country’s most popular artist. I counted four separate shows honoring his centennial, one of them comprised of photographs of the Olson house in Cushing, a veritable shrine for Wyeth fans.

Two exhibitions are based primarily on Wyeth’s drawings. Some will find these exquisite, but even while admiring the technical aptitude I’ve always found much of Wyeth’s draftsmanship a bit bloodless, or at the very least, precious. I’m reminded of the comparison Kenneth Clark made between Leonardo’s drawings and the life studies of Durer: the latter were very good, but dwelt in the scrutiny of the specific, without Leonardo’s grasp of the abstract organic patterns that run through nature. That’s a good way of summarizing what’s missing here. In Wyeth there is nearly always a tenuous balance between life force and desiccation. It’s long surprised me that an artist with so strong a depressive vein would become so popular in America. Surely the mistaken apprehension that Wyeth’s painting looks “just like a photograph” plays a role, but perhaps we identify more strongly with a sense of barrenness than I’d thought.

The most impressive of the Wyeth shows is installed in the eponymous center, and chronicles his watercolors. Mostly the paintings that stand out are from two periods, the latter including those, like Betsy’s Beach, that he painted towards his ninetieth year. At the other end of his creative life are the paintings Wyeth made before he became allergic to chromatic saturation and, to put it bluntly, exuberance. Later he explained that he abandoned the loose style because it was too easy, but there’s more to it, and it’s not novel to suppose something inside him changed after the accidental death of his father in 1945. Early paintings like Big Spruce, Clouds and Shadows and Artist Sketching are reminiscent of Homer’s watercolors in their freewheeling approach, but also because violence and tragedy exist tacitly, without the melancholic and sometimes maudlin strains that often suffused his work for the next half century. There was profundity in what came easily to Wyeth, and I think we lost something when he renounced his youthful spirits and got all serious on us.

Marguerite Zorach—An Art-Filled Life is on view through January 7, 2018. Andrew Wyeth: Maine Watercolors, 1938 to 2008 is on view through December 31, 2017.