[1]

[1]We forgive our parents many things, but I may never forgive mine for raising me in South Florida. Despite having escaped its drenching climate and congenitally maladroit drivers long ago for the northeast, familial ties beckon my return several times a year. Upon arrival last week, my suitcase was confused with an identical piece of luggage on the shuttle from the West Palm Beach airport to the car rental, which later in the evening entailed a meeting at the Avis counter between two chastened and relieved travelers, exchanging Samsonite bags while spectacular forks of lightning flashed outside. With possessions reclaimed, I pulled up to my hotel in a monsoon, the rain cascading sideways, palmetto trees lashed helplessly by the wind. It was the kind of flash storm that is daily summer fare in these parts.

It had been nearly twenty years since I last visited the Boca Raton Museum of Art, when they put up a show of my landscape paintings (okay, we like some things about South Florida). This week I returned to find the museum much expanded and looking a lot more high rent, having moved from the building it once shared with its art school to more stately digs at Mizner Park downtown. What brought me back is an exhibition of work by Nicolas Carone, who was a mainstay of the New York art world through the second half of the twentieth century. Carone was a first-generation abstract expressionist, who never renounced the figure. “We always worked from nature,” he once said. “No matter how abstracted the drawing became, it came from nature. And I believe in that, by the way.” His education must have been damned interesting: an early mentorship with Leon Kroll was superseded by the influence of Hans Hofmann. That’s a whipsaw move from classical figuration to vanguard modernism.

[2]

[2]I didn’t know any of this when I met Mr. Carone sometime in the early 1980s. Fresh out of school and looking for a break, I called him at the suggestion of my father. The idea was that he could be of some professional assistance, but the meeting was a bust from the start. Nailing down an appointment was proving difficult, so I showed up one day at the door of his studio building in lower Manhattan. Understandably, Mr. Carone wasn’t too thrilled by my unannounced appearance. He led me into a spacious studio, where we sat at a table and I showed him photos of my figure work; his reaction eliminated any hope of a gallery referral. What I recall from that mutually uncomfortable session was his annoyance with the literalness of my imagery. Mr. Carone was a prominent teacher, and he tried an instructional approach. An anecdote was summoned to exemplify the artist’s spirit: one night many years past, he sat in the Cedar Tavern talking with his friend, Jackson Pollock. After a long while he realized that Pollock had spent the balance of the evening rearranging the contents of a cigarette ashtray with his fingers, always engaged in the creative process. This was offered as a seminal lesson, though it sounded to me like an odious cliche. Perhaps, I thought, Pollock was just bored. Or in his cups. The separation between Mr. Carone and myself was more than generational. To paraphrase a line from Jack Levine, we didn’t even worship at the same temple.

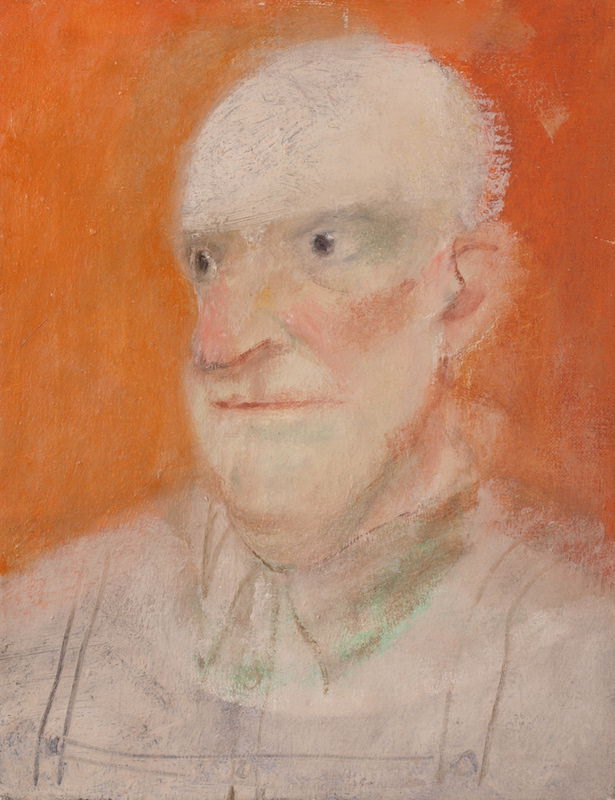

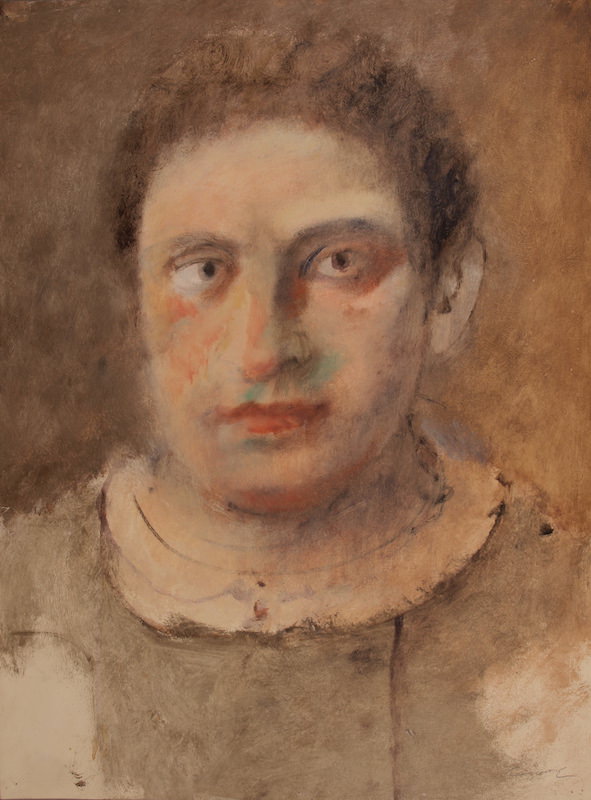

So much for personal history as preamble. Carone’s range as a painter is exemplified by the selection here: a few earlier pieces in the action painting mode, some mid-career imaginary portraits, and the late, linear paintings for which the show is named. Physically and psychologically odd, the portraits fascinated me (the two images provided here by the museum are good, though not my favorites). They bear a resemblance to the paintings of his friend John Graham, but are less distinctive, or more properly, less definitive—an endearing fact about Carone was that he grew disillusioned with the gallery game, and stopped exhibiting. When an artist paints in privacy as opposed to answering show deadlines, the outcome tends to favor the personal over the public. The portraits are more introspective than his larger, aggressive canvases. They are still painterly, but tender, fragmented, and a bit haunted.

[3]

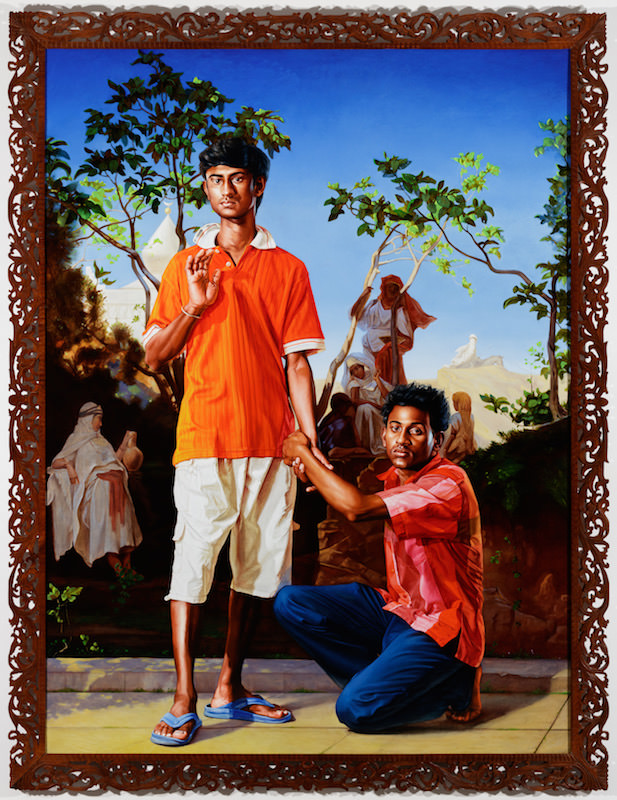

[3]By contrast, nearby hangs a consciously public piece by Kehinde Wiley. Acquired by the museum this year, presumably in the wake of his much publicized Obama portrait, it is the most grandiloquent of Wiley’s “World Stage” canvases representing Sri Lankan youths. The painting is a highly realistic narrative, dominated by two full-length portraits. The backdrop is a nineteenth-century Orientalist canvas that was painted at a time when Muslim territory was subjugated by European colonialism. Color is cinematically heightened, and forms are studiously modeled in the new-academic manner.

Both Carone’s and Wiley’s paintings contain art historical references. For Carone, Italian Renaissance art was a touchstone; Wiley refers to Italian painting, too, but this large canvas is a meta spin on the French academic atelier. Carone turned away from the commercialism of the art world, whereas Wiley embraces it, employing a staff of apprentices to do some, or much, of his painting. It’s Carone’s portraits that I prefer, because the personal generally is more interesting to me than the rhetorical, and also because I’ll take a picture painted in an open manner over one that’s polished to a shine six days out of seven. The exception being any portrait by Ingres.

In different ways, both artists carved eclectic paths. Carone studied and practiced figurative and abstract art, and founded or co-founded several schools, including the New York Studio School. Wiley is of Nigerian heritage, studied in Los Angeles and Russia, and has maintained studios in Harlem and China. There is no straight line to becoming an artist. Some years ago I read an online blog written by an art student, who’d been included in a weeklong master class overseen by Antonio López García. In his youth, López García was at the forefront of a movement to revive representational art in Spain; he may be the preeminent living figurative artist. The student asked about atelier programs, and López García’s response, which I’m paraphrasing from memory, was adamant: an artist learns best not through the auspices of the right school, but by dint of individual trial and error.

I mention all this because students sometimes search for a single teacher or system, hoping to resolve complexities of methodology and philosophy. Which brings me back to South Florida, and the formative influence of my first life drawing teacher, a Latin artist who’d studied in Italy and South America, and who appreciated the old masters as well as modern art. He encouraged me to start a drawing by prioritizing abstraction over description. In retrospect, this was an essential foundation for my later, narrower focus on nineteenth-century art, and to the classes I eventually took in New York. I couldn’t have found a better teacher. Turns out that being raised in South Florida, I was in the right place at the right time.

- [Image]: https://asllinea.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/NC-Untitled-1985-Oil-on-linen.jpg

- [Image]: https://asllinea.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/NC-Untitled-1985-oil-on-gesso.jpg

- [Image]: https://asllinea.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/IMG_5109.jpg