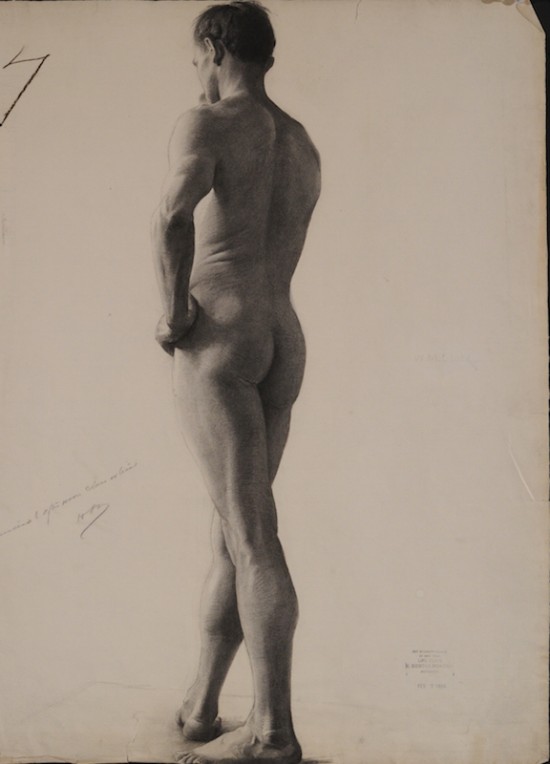

Early life drawings are among the most inspiring works in the permanent collection of the Art Students League of New York. Reflecting the high standards of the school’s founding artists, these student drawings underscore one of the primary reasons for establishing the League: the need for more opportunities to sketch the live model. Life drawing had been a cornerstone of the curriculum at the École de Beaux-Arts in Paris, where many of the League’s early instructors had studied. In America of the 1890s, it was also essential training for artists seeking work on projects like the high-profile monument and mural commissions awarded to some of those same teachers, including Augustus Saint-Gaudens (1848–1907), H. Siddons Mowbray (1858–1928), and Kenyon Cox (1856–1919).

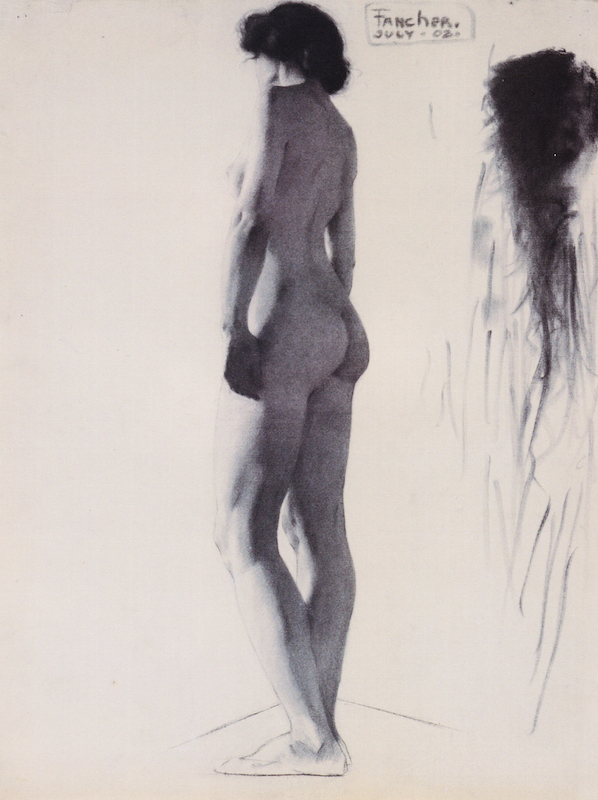

This exhibition, Drawing Lessons: Early Academic Drawings from the Art Students League of New York, presents life drawings by students of Cox, Mowbray, Frank Vincent DuMond, George Bridgman, and others, done between 1889 and 1924. Executed in charcoal, these works survived because of their recognized excellence, retained by the League in exchange for tuition scholarships and prizes, often noted in their margins. Framed and mounted on classroom walls or preserved in portfolios, they served as a learning resource and an important record of the school’s accomplishments.

The League’s emphasis on life drawing established its connection of the classical tradition in Western art that was stressed in European art academies. It also reflected the founders’ determination to become a leader among American art schools. In his 1886 report on the League’s first decade, President Frank Waller described the school’s life classes as unprecedented and “historic” in American art education, and he proudly listed the number of poses and hours struck for each class the preceding year.

The League had emerged in 1875 as a protest to the National Academy of Design’s school. Intermittent financial problems had plagued the Academy for years, and the Academicians assigned to teach in its school were often indifferent instructors. In 1870, the school hired Lemuel Wilmarth (1835–1918), a committed and talented drawing instructor. However, when the Academy announced five years later that he would not be rehired due to lack of funds, a group of students took matters into their own hands and established the League. Wilmarth volunteered to teach for free until the new school had time to take hold.

Wilmarth eventually returned to the Academy when its school reopened, but the League saw its enrollments grow. By 1885 it could boast a faculty of drawing instructors that included William Merritt Chase, Walter Shirlaw, William Sartain, Thomas Dewing, Kenyon Cox, and J. Carroll Beckwith. Thomas Eakins offered lectures on anatomy illustrated with a skeleton, live models, and casts borrowed from the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Art. Waller’s report noted that reproductions of well-known artworks, as well as original life studies, were hung on the League’s studio walls for inspiration. Some of these were “exile contributions,” drawings sent back by League students fortunate enough to study abroad as a donation to the school’s teaching resources. Over time, outstanding drawings done in the League’s own studios were added to this body of work, forming the nucleus of the permanent collection.

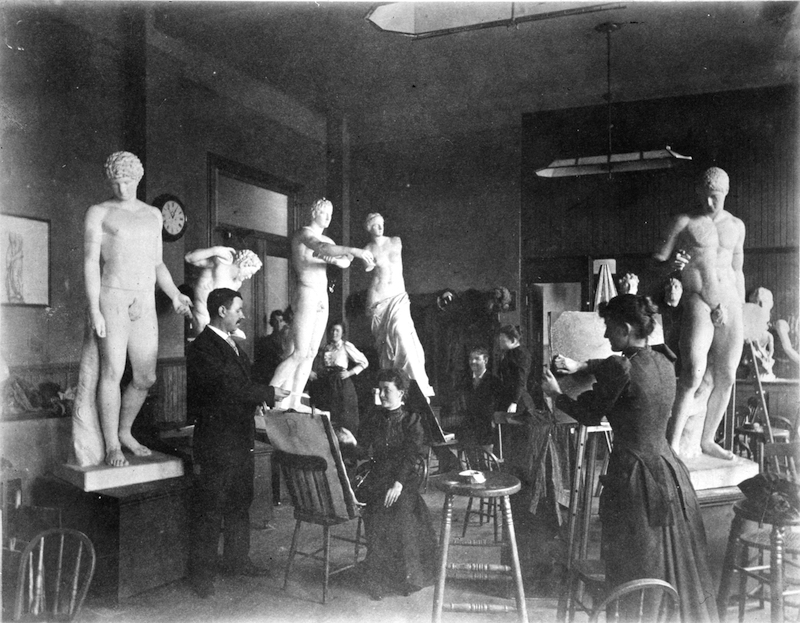

These works attest to Waller’s observation that the “severest study in the school” took place in its life classes. The figure drawings required just for entrance to those classes had to meet rigorous standards. An Examining Committee of one professor and two students reviewed these submissions, and their unanimous decision was final. In 1878, a preparatory class in drawing plaster casts was introduced “to feed the life classes.” This class was called “Antique Drawing” because some of the casts were reproductions of classical Greek statues. Drawing these lifeless forms, beginners mastered basics such as modeling with light and shade.

The importance of life drawing was further reflected in changes in the League’s membership requirements (not all students were members). Early members had only to pay dues and sign the school’s constitution. An 1883 amendment further stipulated that applicants attain “the standard in drawing required of students in the life class.” A “Candidate for Membership” card is still pinned to one of the drawings in the League’s collection. This requirement was eventually dropped.

The founding of the League and other arts organizations in the 1870s reflected a cultural blossoming in this country often described as the American Renaissance, spanning the 1870s to the 1930s. American artists returning from top-notch training in Munich or Paris sought to address the country’s cultural limitations, particularly in the visual arts, with the establishment of schools modeled on the European academies. In 1875 there were ten art schools in the country; by 1882 the number had jumped to thirty-nine, and there were also fourteen university art schools and fifteen decorative art societies.

Academic training in Europe had exposed American artists to Western art history, particularly Classical and Renaissance art. They understood the importance of the figure in that art and therefore in the schooling of an artist. Life drawing was essential for anyone aspiring to the prestigious genre of history painting, which embraced biblical, mythological, and historical subjects. It was also fundamental training for allegorical works by muralists such as Kenyon Cox, who had studied at the École des Beaux-Arts for five years. The League’s earliest course catalogues stressed this lineage, listing each instructor’s European mentor. Cox, for example, was described as a student of French instructors Carolus-Duran and Gérôme. In their own work and in their instructional approach, artists like Cox linked American art to the history of Western civilization. It was an exciting time to be an American artist, and Waller described the League students of 1885 as “earnest and active.”

For most American artists who could afford to go abroad in the late nineteenth century, Paris was the destination of choice. Its museums offered immersion in the great art of the past, and its galleries and annual salons presented the spectacle of contemporary art. As art historian H. Barbara Weinberg has pointed out, American artists set out to rival their French counterparts whose work was being purchased by American collectors. Acceptance to the Paris Salon, or mention in a Parisian periodical, which was often quoted in the American art press, could also boost one’s artistic stature.

Ambitious art students set their sights on the prestigious and competitive École des Beaux-Arts. Failing acceptance there, they could enroll in schools such as the Académie Julian or individual artists’ ateliers. The entrance test for the École–the concours des places–involved drawing from the nude. From about 400 applicants, 130 gained admission, but their security was short-lived. These students had to win a medal in a more advanced competition, the concours d’émulation, or else compete every semester in the concours des places to continue their studies. Those who won the concours d’émulation were then eligible to compete annual for the Prix de Rome until age 30. That honor earned an artist four years at the Villa Medici in Rome. As proof of progress, one work had to be sent back to the École annually. These works were exhibited “to show the absorption of classical and Renaissance art” and became property of the French state.

The basic weekly exercise at the École was a full-length life drawing, known as an académie. But before one could enter the life class, a beginner first copied engravings of figurative subjects and then advanced to drawing plaster casts. This was done in strict sequence, from individual body parts to full-length figures such as the Belvedere Torso. The drawing practice thus doubled as a lesson in Classical art history. Drawing from the antique was considered so beneficial that even those admitted to the École’s life classes were regularly required to draw from cast in the course of their studies.

In the life classes, model were often posed to echo well-known statues from Antiquity. This made it easier to resume poses, which lasted for about six days. Students worked four to five hours a day. One’s seniority or success in class competitions determined his position vis-à-vis the model. More advanced students could choose to work at a distance so that they could create a full-length image; beginners seated up close could only do head and shoulder studies.

During séances de correction, instructors addressed problems in accurate anatomical representation and proportion. Albert Boime, an authority on educational techniques at the École, has observed, “Conceptually, the correction was linked to the notion of perfection rooted in the admiration of Antiquity. Correcting a drawing … implied the adherence to classical proportions. Correction therefore denoted perfection…. This explains the Academic horror of strict observation of the model; when a pupil copied a figure’s defects, he committed a double sin in terms of Academic criteria: admitting ignorance of Antiquity and rejecting the concept of correction.”

Many aspects of the École system were replicated at the League. Lemuel Wilmarth, the League’s first teacher, had been the first American pupil of Jean-Léon Gérôme at the École. Perhaps on Wilmarth’s recommendation, others followed who later taught at the League: Kenyon Cox, Douglas Volk, George de Forest Brush, J. Alden Weir, and George Bridgman. Though these Americans also studied with other teachers in Paris, Gérôme was extremely popular and influential. His demanding standards in draftsmanship were legendary among them. Urging them to study nature with an inquiring eye, Gérôme also stressed unified, orchestrated compositions and recommended the study of Renaissance art. His students began their figure drawings as general outlines, working in details, and shading section by section, beginning with the head. The League’s early life drawings reflected a similar approach. Students used both vine and compressed charcoal and learned to shade areas by smudging the charcoal with the compressed paper crayon called a “stump.”

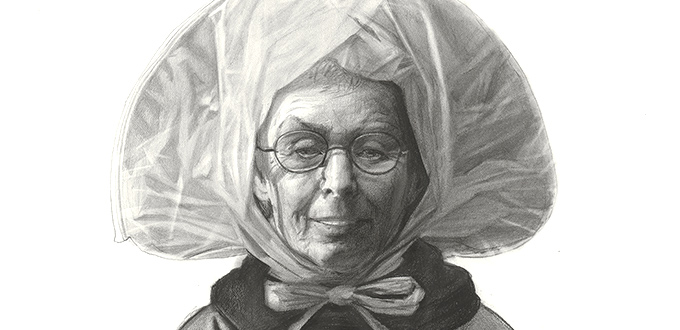

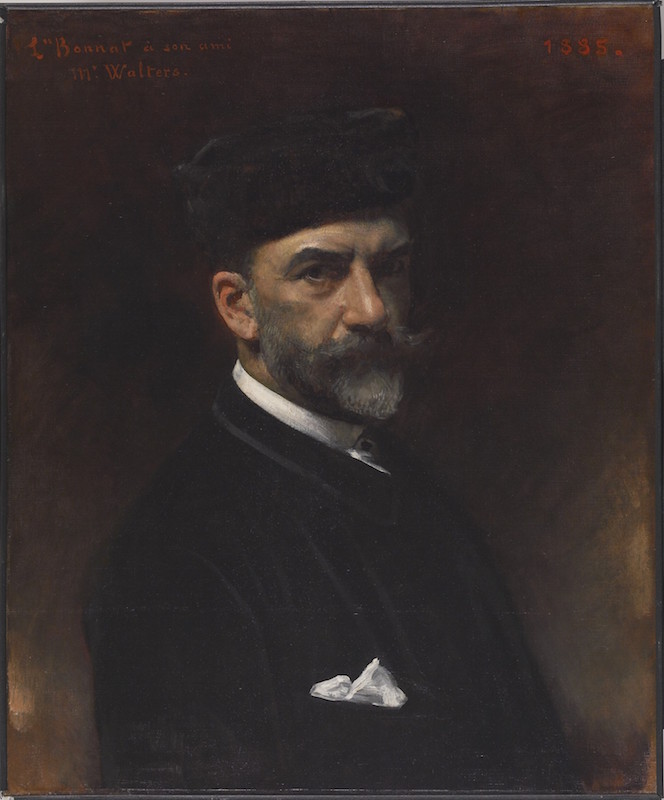

Other League instructors–H. Siddons Mowbray, J. Carroll Beckwith, and William Sartain–had studied in Paris under Léon Bonnat, who emphasized a naturalistic approach and a focus on contemporary life. He employed models of all ages and, unlike the École, did not use the academic poses based on Antique sculptures. Mowbray remembered the “stern realism” taught by Bonnat, writing, “No one did a thing without the model” in his class. When Sartain asked his former mentor in 1880 about the virtues of teaching from live models or Antique casts at the League, Bonnet wrote back, “It was only by studying … the living model that the Greeks arrived at perfection…. Let the student abandon himself to the study of the living model… analyze and measure…. Let him study anatomy and understand the causes that swell or diminish muscles.”

The strong liaison between the French schools and the League emerges in the memoirs of Louise Howland King, who entered the League in 1883. It should be noted, however, that King’s very presence in League classes represented a strong break from the École, which did not admit women until the late 1890s. From the League’s start, women enjoyed their own classes in life drawing, where male models were discretely draped.

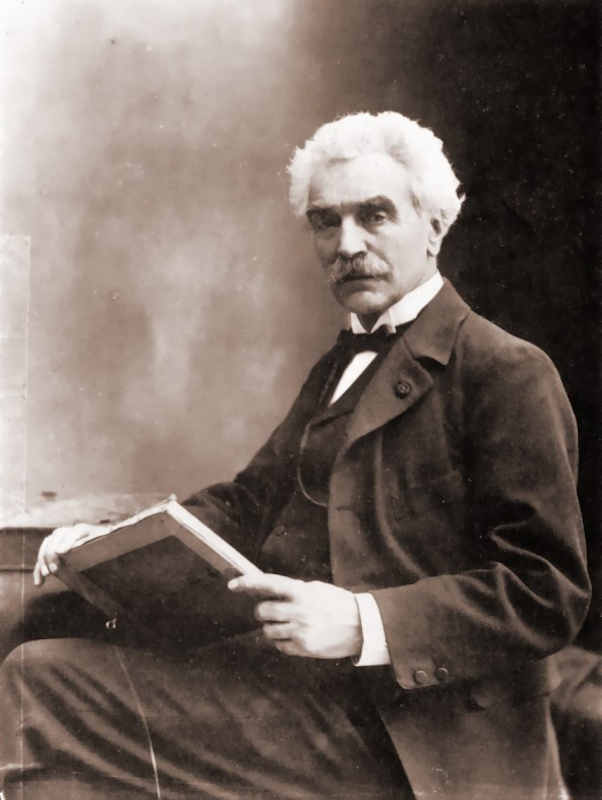

King recalled frequent student discussions of the excellent work done by American artists studying in Paris, including Cox, Mowbray, Beckwith, and J. Alden Weir. Indeed, “even before their return to the States, they were casting their shadows for them,” she wrote. Known for his outstanding draftsmanship, Cox was hired as the men’s life drawing instructor at the League in the fall of 1884. “It was with a deep breath and some misgivings,” King, his wife, reminisced, “that the Men’s Life Class broke with the old tutelage and put themselves under the guidance of this new blood.”

Cox taught life drawing at the League until 1909, introducing the exacting standards and respect for laborious training absorbed during his three years of study with Gérôme. Impatient and sometimes harsh, he often erased and redrew students’ work, and he did not hesitate to send them back to the antique class when their life drawings did not measure up. Cox introduced the French tradition of the concours to the League soon after joining the faculty. These competitions highlighted outstanding work in the individual classes. In at least one case, a concours was used to demote students from a drawing class and admit others from the waiting list.

In their murals for public spaces, artists like Cox and Mowbray offered students models of how their life drawing studies might bear fruit. The boom in public building and decoration after 1890 created many opportunities for talented figurative artists. Cox had established a national reputation as a muralist, beginning with his work for the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago, which led to commissions for numerous state capitol buildings and the Library of Congress. Closer to home, League students enjoyed a massive exhibition celebrating the school’s twenty-fifth anniversary in 1900, including designs and cartoons for mural decorations by Cox, John La Farge, and others that filled the entire Vanderbilt Gallery (now League studios 15 and 16).

Cox’s murals demonstrated his conviction that idealized nudes could powerfully communicate concepts such as wealth or education to a broad public audience. As an articulate and respected critic, Cox defined “classical art” for his age with qualities that were elected in his own work: permanence, clarity, continuity with the past, reason, and disciplined emotion.

In his essay, “The Nude in Art,” Cox advocated a blending of idealism and realism in portraying the human form, ruling out “photographic copying,” but warned artists to also “beware of the false ‘idealization’ which consists of preferring the ready-made formulas of others to the natural beauty before [you].” In his 1889 design for the League’s logo, still in use today, Cox represented Art as a draped, seated female nude sketching on a pad.

H. Siddons Mowbray’s League classes clearly absorbed the realism espoused by his French instructor Léon Bonnat. This is particularly evident in the nearly photographic drawings by several students working under Mowbray in the 1890s. His pride in his students’ work—and in the League—registered in his unique personal stamp that appears on some of the student drawings. Instead of his own signature, the traditional sign of an instructor’s approval, Mowbray mechanically recorded the school, class, instructor, and date of the work.

In his own highly recognized mural commissions for the Morgan Library, the University Club, and private residences, Mowbray moved toward a more classical, idealizing approach to the figure. An 1897 exhibition at Knoedler Galleries in New York presented forty Mowbray works, including literary illustrations and sketches for wall panels in the C.P. Huntington residence representing Music, Literature, Tragedy, Comedy, Electricity, Astronomy, and Painting.

Frank Vincent DuMond (1865–1951), who joined the League faculty in 1892, preserved a stronger commitment to naturalism, having studied at the League with Sartain and Beckwith and in Paris at the Académie Julian. DuMond had worked as a newspaper illustrator in New York before heading to Paris, and he continued to produce literary illustrations throughout his early career. His academic training nourished his success in portraiture and large figure paintings of religious subjects.

As the number of drawing instructors at the League increased, philosophical differences and rivalries emerged. In a 1906 letter to his wife, Kenyon Cox wrote of his students’ success during the end-of-the-year scholarship awards and took aim at fellow instructor DuMond. “My life class work is undoubtedly the best in the school,” he wrote. “[DuMond’s] policy of admitting pupils who haven’t had any previous training is not bearing fruit, and his class gets weaker and weaker, while all the serious students come to me. Every one of the prize winners has worked up through the antique and learned something.”

Though DuMond had taught an antique class early in his teaching career at the League, his later decision not to require it for admission to his life class actually reflected European trends. By 1899, most Parisian schools had done away with cast drawing. Gradually, the League changed some of its antique classes to life classes. After Cox’s retirement, proficiency in the antique was not required for entry into any of the League’s life classes, although the antique class was offered up until 1950.

By the time Cox retired from teaching at the League, others had joined the faculty as life drawing instructors, including George B. Bridgman, Edward Dufner, and Kenneth Hayes Miller. Chief among these was Bridgman, who taught at the League from 1898 until 1943 and authored several books on constructive anatomy. A Gérôme student, Bridgman developed a sculptural approach to the figure that emphasized its capacity for motion. A good drawing had to show action, Bridgman stressed, suggesting the “flexibility and elasticity which is characteristic of the human figure in life.” Likely impressed by the photographic experiments of Eadweard Muybridge and the advent of motion pictures, Bridgman wrote:

The slow, continuous moving picture has given us a new appreciation of rhythm

in all visible movement. In these pictures of pole vault or steeplechase we actually

follow with the eye the movement of every muscle and note its harmonious relation to the entire action of the man or horse. So to express rhythm

in drawing a figure we have in the balance of masses a subordination of the passive or inactive side to the more forceful and angular side in action,

keeping constantly in mind the hidden subtle flow of symmetry throughout.

Challenging his students to capture the harmony of human motion, Bridgman posed his models twisting and turning, and he advised them to “make it swell,” referring to the tension of one part of the body pulling against another. His students’ works often bear in their margins his telltale, serpentine drawings offered as corrections.

Like Bridgman, subsequent instructors left their individual stamp on the League’s life drawing classes. In 1951, students could choose to study life drawing with realists Reginald Marsh and Kenneth Hayes Miller, modernists Will Barnet, Yasuo Kuniyoshi, and Vaclav Vytlacil or eighteen others. The League’s tradition of acquiring students’ work for its collection thus created a register of changing styles and instructors’ vantage points over the last 134 years. In this context, however, the early life drawings stand out as a group, reflecting the fervent aspirations of the first few generations of League students—both for their school and their individual careers.

This essay appeared in the catalogue accompanying the exhibition Drawing Lessons: Early Academic Drawings from the Art Students League of New York, which was organized by curator Pam Koob, in 2009.