The Met Breuer has put together a cohesive and powerful show in Marsden Hartley’s Maine. It’s cohesive by dint of theme, but also because Hartley’s best work, while undergoing changes in palette and mood over the course of his working life, was consistent in its grasp of the distinctive image. This comes as rather a surprise after reading the artist’s correspondence, for Hartley was deeply insecure about his standing—there was a period when he compared his painting to Picasso in an effort to convince himself of eminence—as well as the more mundane but vital matter of selling art. The need for reassurance was constant, his self-absorption exasperating. His pre-World War I infatuation with Germany doesn’t play well, either. A Hartley scholar told me that while writing about the artist, he fantasized that the ship carrying him back to the U.S. in 1916 had sunk.

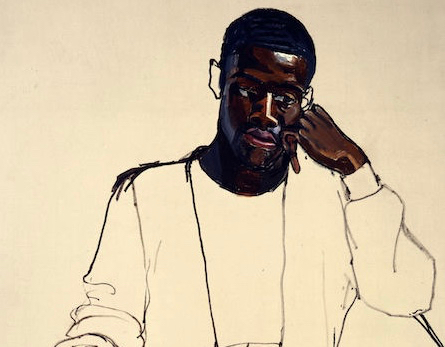

Hartley’s Maine paintings were based on the landscape of his home state, boiled down to a series of iconographic images of mountains and oceanfront. He was able to channel two of his greatest immediate predecessors, Albert Pinkham Ryder and Winslow Homer, melding mysticism and solid form, or, more precisely, the impact of solid form through graphic symbols. To these traditional landscape elements he added another that hadn’t previously received much attention from American artists: homoeroticism, in a group of stylized odes to the male body electric. Critics for the most part dodged the issue while admiring the paintings’ masculinity. (I’m reminded of how long art historians were uncomfortable with the subject: Lloyd Goodrich, generally superb and always readable in his 1982 biography of Eakins, defended his subject’s heterosexuality by noting the lack of feminine qualities in his painting, and left it at that). In art as in life, Hartley didn’t connect easily with individuals, and many of his figures are hardly more than brightly-colored manikins, but the Met Breuer show has the best of them in his memorialized portrait of Ryder, Madawaska—Acadian Light-Heavy and Canuck Yankee Lumberjack at Old Orchard Beach, Maine. Despite their ridiculous physical exaggerations, the monumental nude that fills the picture plane and the bow-legged bather seen against a summer sky are among the most memorable male figures in American art. They are idols that would have been unrecognizable to Ryder or Homer, both of whom were still alive when Hartley painted his first Maine scenes in the years before 1910.

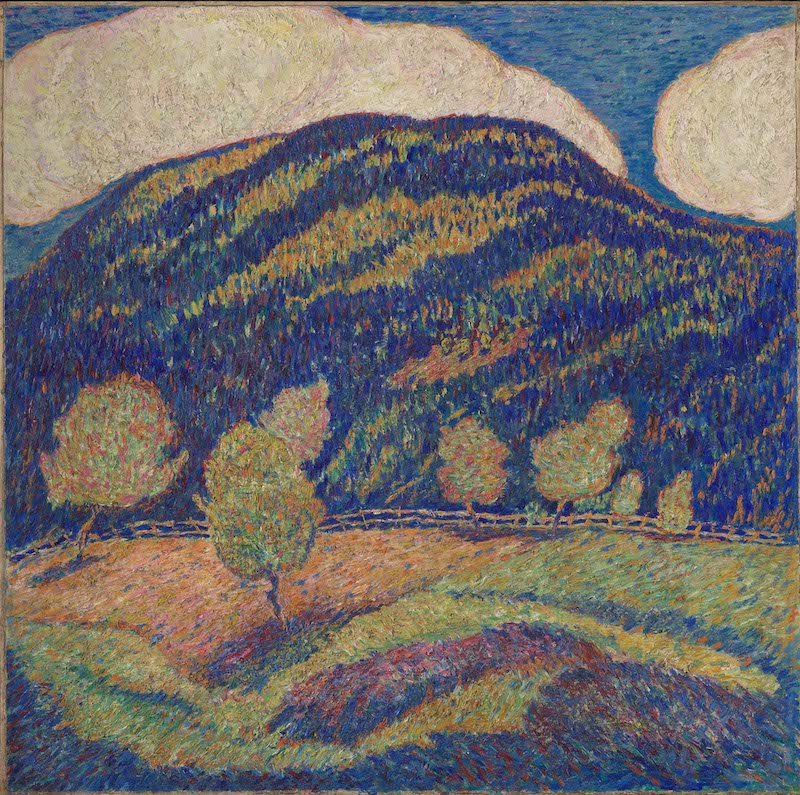

The early landscapes feature an ostensibly impressionist palette, and that’s as far as the similarity goes. Hartley was never interested in the transient impression—as much is clear from the quick drawings that open the show and account for its sole sour note—even when he painted sunlight breaking in staccato pools across a stubbled mountainside. He was always hunting the resolute image, a perfect pictograph, and he largely succeeded. The early Maine works, inspired by inland topography, are dense tapestries built on thousands of thick, small brushstrokes. The design that attracted him goes back to the Hudson River School, but in Hartley’s versions is flattened to basic recognizable patterns: a foreground plane of land or water, then some middle-distance trees followed by a dark mountain and a high horizon line beyond, with stylized clouds jammed in at the very top. It was a theme he repeated obsessively and to varied effects. In 1909, vivid colors gave way to a “Dark Landscapes” series which bore the moody influence of Ryder, and perhaps something more. Stieglitz claimed that Hartley was considering suicide while painting them.

For a long time Hartley couldn’t get far enough away from Maine and unpleasant memories of childhood, hence the chronological gaps in the show. After the First World War he returned to Europe for nearly a decade, then moved around the US through much of the 1930s. By then Regionalism was a potent idea, and Hartley had been traveling a long time. He returned to Maine in 1937. In the catalogue for a show that year he wrote,

“I wish to declare myself the painter from Maine….I say to my native continent of Maine, be patient and forgiving, I will soon put my cheek to your cheek, expecting the welcome of the prodigal.”

One wall of the current show is dominated by three similar large oils inspired by the crashing surf at Schoodic Point, a less traveled section of Acadia National Park adjacent to Mount Desert Island. In these paintings Hartley reconciled the influences of Homer and Cézanne; the Met has loaned the former’s Northeaster for comparison. Viewing the crashing waves at an angle, the Homer is both naturalistic and substantial. Hartley’s versions take the ocean straight on. They are hauntingly visionary, their symbolic shapes vastly more sophisticated than in his pre-1910 images, and they hold up better than the marines of the many painters who took Homer’s influence more literally. Cézanne comes into play in the abstract syntheses of forms, hatched brushstrokes and the shapes of the upthrust foam, as if the triangular bulk of Mont Sainte-Victoire had been reconstructed from water and viewed through an embankment of serrated rock projections. In their dramatic pessimism they give visual expression to thoughts Hartley confided in 1939: “I am pent up in a lot of things….I am a first class hater now—I hate life and I hate art—lots of men turn on their wives later in life and never speak to ’em—I’ve been married too long to art to tolerate the bitch any longer.” Tolerate he did; those last years in Maine constitute a memorably prolific stretch.

Of a sunnier disposition is a series of images that may represent Hartley’s most direct reply to Cézanne, in the form of Mt. Katahdin. Then again, the allusion to Cézanne is just a point of departure, for the abstraction of shape in the Katahdin paintings is as decisive as a cut-out silhouette. At the least, the late works reflect Hartley’s assimilation of multiple influences from European and native modernism into a personal expression; I even thought of Georgia O’ Keeffe, another artist who communicated in hard-edged symbols, with whom Hartley had competed years earlier when both were represented by Stieglitz. There are also several views from Hartley’s window, with an obvious nod to Matisse. Yet all these associations are for us, as they were for Hartley, merely touchstones. The forms he distilled from nature were, in the end, products of his own reinvention.

Meeting the aging Hartley at a reception, Fairfield Porter found him “bitter and contemptuous,” but was of the opinion that “he is a real artist, who deserves better treatment from the world.” Hartley would have undoubtedly agreed. The current show at Met Breuer confirms that his works number among the very best paintings of Maine, and of American modernism.

Marsden Hartley’s Maine continues at the Met Breuer through June 18.