[1]

[1]For the last twenty years I’ve been spending parcels of time during the milder seasons in midcoast Maine. All told, in about nine months of accumulated vacations I’ve painted dozens of views of the coastline, yet managed to avoid making the trip out to Monhegan Island. A little piece of rock fourteen miles out in the Gulf of Maine, Monhegan is the Mecca for landscape painters on the eastern seaboard; since the population is around seventy, in the summer months it may be one of the few communities where visiting artists outnumber residents. The issue for me hasn’t been proximity, since more often than not I’ve stayed in or near towns that send mailboats out every day. The truth is I’ve been loath to make the journey on a wave-tossed skillet. Also, Monhegan’s spectacular cliffs and jagged shoreline have been painted so many times and so well—from the paintings of others, I know Blackhead and Whitehead and Pulpit Rock and Manana and Fish Beach and Gull Rock by heart—that it seems to me I’d have nothing new to contribute, especially in a few days as a painting tourist.

For the romantic ideal of the artist leaving the workaday world behind to rough it in a remote and dramatic place, there may have been no better prototype than Andrew Winter, whose work is the subject of a show this summer at the Monhegan Museum. Some backstory is helpful. Artists have been working on Monhegan since the mid-1800s, but the place got hot after Robert Henri paid a visit in the summer of 1903. When he returned to New York he urged his students to go, and they did. Edward Hopper and George Bellows had a field day on their visits, filling small wood panels; Bellows and Henri each produced hundreds of paintings during their sojourns. Rockwell Kent decided to stay, building a home and studio now owned by Jamie Wyeth.

[2]

[2]Winter was not directly associated with Henri and his followers, but stylistically he fits into the early twentieth-century realism groove, and by nature he was suited to life on the island. He was born in Estonia and spent years working as a merchant seaman, sailing on the ocean for months at a time. The work was rough; Winter once lost a friend in a hurricane and another time jumped into a rowboat to save the lives of four men after a collision at sea. In 1920 he settled in New York, and studied first at the National Academy and later at the Cape Cod School of Art. He met and married Mary Taylor, a fellow painter, and together they started visiting Monhegan in the early 1930s. After establishing a successful career as a fine artist and muralist, in 1940 Winter left his apartment on East 59th Street, and he and Mary moved to Monhegan.

[3]

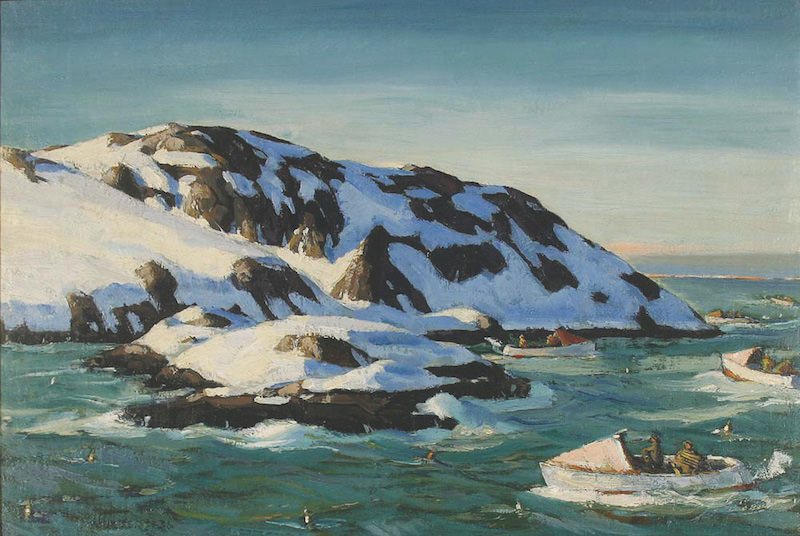

[3]Winter became so inextricably linked to Monhegan that his paintings of the island eclipse everything else he did. For obvious reasons, the Monhegan work has been compared to that of Homer and Hopper. Notwithstanding the assured drawing, what often distinguishes Winter is an aversion to economy. Seaward Cliff, for example, presents a multitude of high value contrasts between snow and rocks, sea foam and cliffs and land and sky. These staccato tonal changes present a series of digressions from the culminating point, the meeting of distant headland and ocean. Similar issues are at play in First Set, Monhegan, where the snow sits like intermittent frosting on a lopsided Wayne Thiebaud cake, and Home Again, with its complex interplay of light and shadow. One of the reasons all this works is that Winter’s elaborations strike a visceral rather than photographic note—he wasn’t painting detail for its own sake, but as it appealed to his energetic spirit. The surfaces of his paintings are roughhewn, emulating the rugged substance of earth and the onrush of breakers. I don’t know that any painter has ever engaged more passionately in the study of snow on rocks, to the extent that it seems like a phenomenon particular to Monhegan. It’s as if he was enumerating the tactile sensations of the island to forestall the silence and seclusion of winter. I’ve seen several paintings by Winter like Seaward Cliff, and busy as they are, I’m crazy about them.

Winter pulled these compositions off with an almost symphonic resolution. The small oils Henri and Bellows churned out on Monhegan were notes of fair weather flings before returning to the city. Hopper’s studies were essays in color and abstraction, warm-ups for the mature work to come. Winter dug in for the long haul, and dug deeply into the specific feel of his home, of granite, wind, snow and water. He’d row around the dangerous rocks to search out better angles. Gulls at Monhegan appears to have been viewed from his boat–we’re plunged into the rough seas of the island’s harbor, alongside fishing boats besieged by gulls. Most painters would have found the inclusion of eight or ten birds sufficient for the job; of course, Winter filled the canvas with them. I stopped counting at three dozen.

In the middle of the ocean, Winter cultivated a garden of solitude, in paintings that are simultaneously dark and boisterous. This was Ashcan School painting transferred to an Arcadian outpost. There are parallels in the work of other contemporary European immigrants, like Jonas Lie and Abraham Bogdanove, the latter who also settled on Monhegan (maybe a play can be written about the dynamic between two Eastern Europeans who ended up painting the same themes on the same little island at the same time). That Winter’s painting is at once completely accessible and tacitly introspective jibes with, or emanates from, his years of maritime travel, its stretches of quiet punctuated by periods of intense physical exertion, even existential peril. It bears repeating that while a lot of artists have seen Monhegan as an idyllic summer sojourn, a handful of others chose to put down roots and see through the least hospitable conditions. Winter was a man for one eponymous season, rockbound but never snowed in. For those who will miss the show this summer, you can do as I have and buy the fine illustrated catalogue. Or you can always see what Winter saw and take a boat out to Monhegan in February.

Reckoning with Nature: Andrew Winter at Monhegan Island is on view at the Monhegan Museum of Art & History[4] through September 30, 2017.

- [Image]: https://asllinea.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/Seaward-Cliff-CMYK.jpg

- [Image]: https://asllinea.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/First-Set-CMYK.jpg

- [Image]: https://asllinea.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/Home-again-CMYK-.jpg

- Monhegan Museum of Art & History: http://monheganmuseum.org