Stephanie Cassidy: There’s a beautiful wide-angle shot of you looking at your work on the walls of Monmouth University’s DiMattio Gallery. You are in the background, walking through a beautiful space, the paintings elegantly lit in a wonderful hanging over two floors. What’s going on in your mind as you’re looking at twenty-eight years of work? There could be a moment of triumph and pleasure but also a paralyzing fear of where to go next and a questioning of whether you’ve reached your greatest potential as an artist. Does a show of this scale push those questions forward in your mind?

Bruce Dorfman: Where to go next is, for me, never an issue at all. I’ve spent my life going along from one piece of work to another, from one year to another. The last piece of work prompts questions that can only be dealt with by doing another piece of work.

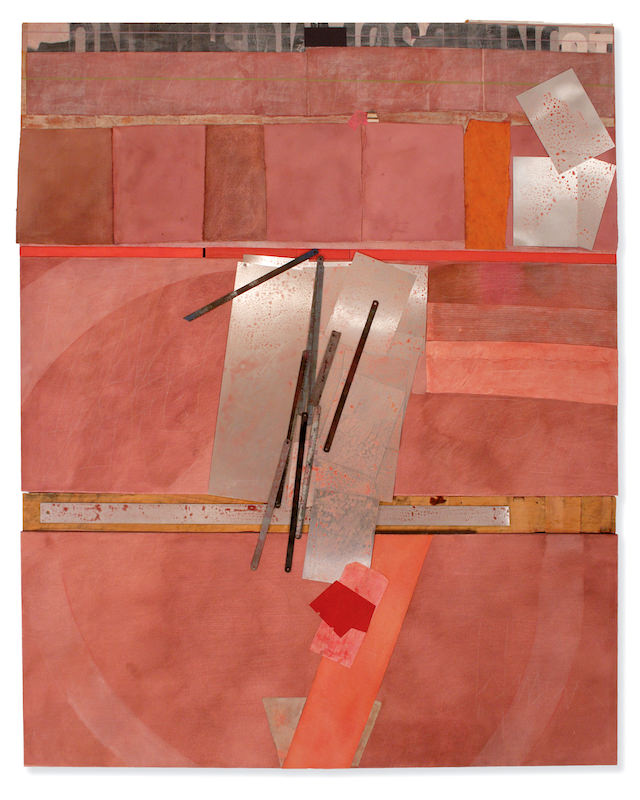

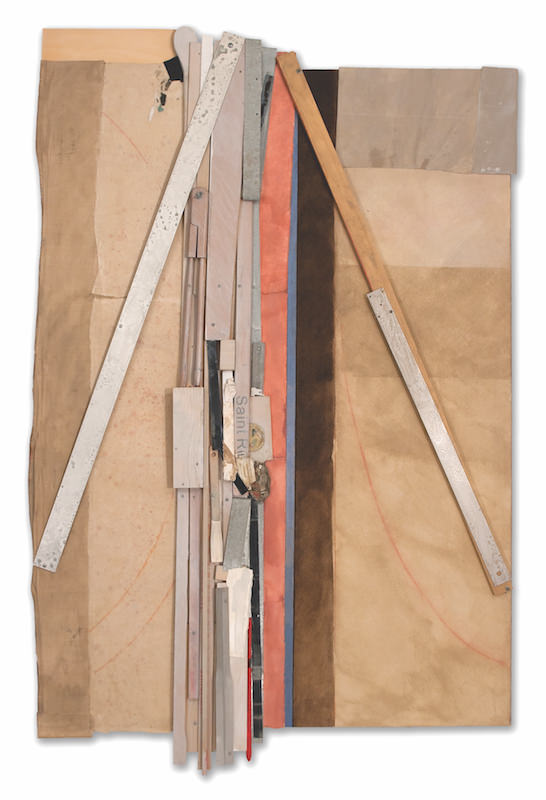

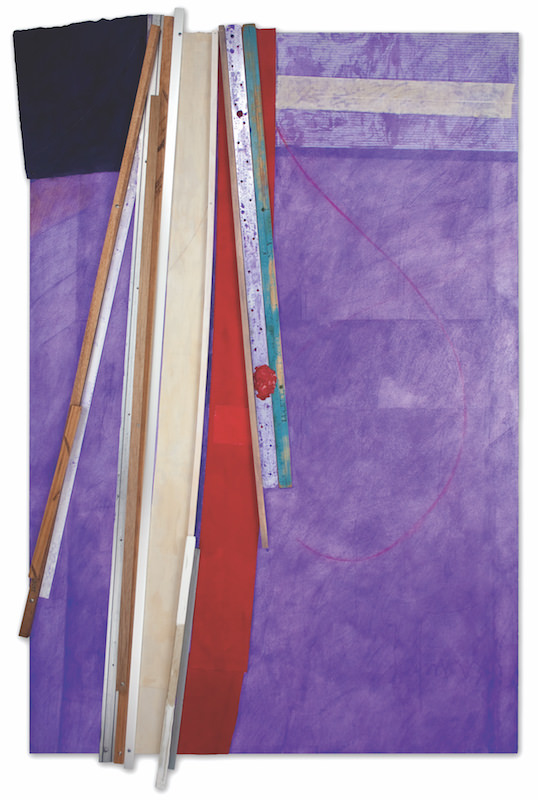

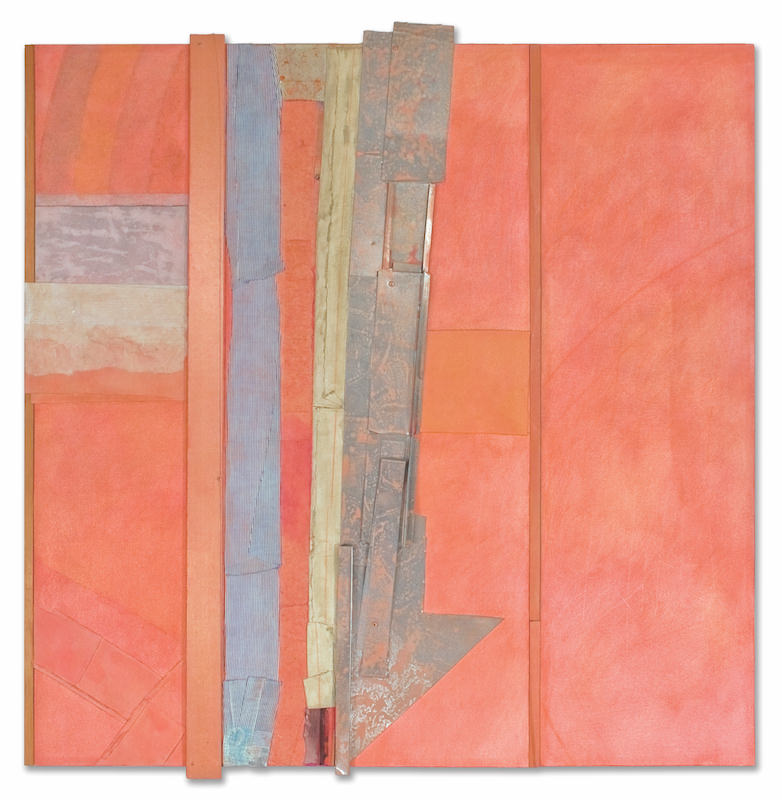

I have never seen that many pieces of my work at one time under any circumstances. The show was curated jointly by Scott Knauer, the director of exhibitions at Monmouth University, Vincent DiMattio, a professor of art at the university, and myself from works taken from the galleries that represent me. There were no works taken from collections at all. Our selections had to be adjusted to the requirements of the space and considerations of whether it might travel to other places. We chose the very best of what we had but did not allow chronology to dictate those selections. The starting point was set at 1988 and the endpoint at 2016. The most recent piece of work was completed just three weeks before the exhibition opened.

If and when the retrospective travels, it would begin with a single piece of work that was completed at the Art Students League, in 1952, a very critical painting that marked an early turning point. Nothing I did between 1952 and 1988 is included.

Cassidy: You’re saying that we can find the origins of your mature composite paintings in this single 1952 canvas?

Dorfman: The painting, Broken Pitchers, was done in Yasuo Kuniyoshi’s and Arnold Blanch’s classes at the Art Students League. That particular piece of work was a turning point.

One of the things that struck me about the show overall is that I was very familiar with the person who painted all these things. I could see constants running through everything, regardless of the shifts of emphasis. There are feelings and ideas and visual qualities that I love, and, apparently, I always have. I’m looking at things that were done quite a while ago, and things that I wrote quite a while ago, which are not very different form what I am thinking now. My ability to express those things, perhaps, is greater at this point, than it was then.

Cassidy: That’s a growth in technical facility or awareness?

Dorfman: It is more a matter of understanding what one needs to bring to one’s work that keeps developing. I think one takes greater risks than one is more capable of, and those risks are better informed than they may have been earlier. The demands become greater. Looking at it, I felt that there was an overall sense of unity within all of the variation that occurred. There was a strong governing sense of personality and choice that ran through the whole thing.

Cassidy: Could either Kuniyoshi or Blanch have predicted the path of your work, taking on these other elements besides paint and canvas, the layered assemblages?

Dorfman: Yes, I think so. Both artists were concerned primarily with the individual in their classes. They did not promote an ideology or specific performance skill of any kind. They were concerned with only the particular student they were talking to at the time, each in a very different way. Charles Alston, whom I also studied with, did that as well. But I walked out of other League classes because they didn’t do that. There was more of a shtick involved and they were teaching to a whole class. There was some kind of ideology or infallible way of doing things that they felt was crucial. And I’ve never been able to understand that point of it at all. I don’t believe in general fundamentals or basics. I simply do not.

Cassidy: If I look at the painting from 1952, what am I going to see that anticipates the work from the 80s and 90s and the other more recent work that you so clearly understand this painting to be a touchstone for?

Dorfman: In that early painting, Broken Pitchers, is a love of color and space and shape. The conversations I was afforded by both Kuniyoshi and Blanch went to a very open-minded idea about works of art incorporating whatever the artist felt was necessary to get to the particular end that they needed to get to. One had to be open to what was right in front of oneself rather than be concerned with whether or not it was consistent with some category or way of doing things. That premise was there with all three of the people whom I worked with.

I was trying to create something that reflected a strong sense of choice and the ability to put it down, to set it, to make it clear in some way. This caused a major turning point for me in my life; being at the League made this possible. It was possible for me to come here and work in classes like that and get the kind of attention and concern that any student might have found necessary.

The white pitcher episode was a turning point. Kuniyoshi often brought to class, very generously, things from home that he loved. One day it was a couple of white stoneware pitchers made in England that he had used in his own work. He set them up in a still life on a table. A group of students was sitting around the table, trying to emulate the still life in some way. Kuniyoshi came in and looked at what people were doing, not saying much. He got upset about what he was seeing, which was an attempt to render instead of trying to see what was there. He took the pitchers, smashed them on the table, and said, There, now, paint that, and left. He didn’t come back until the following week. I took that very seriously. It was a hell of a sacrifice for him to make in order to try to give us something, in terms of an understanding. That struck me in a very big way. I thought I should really make a greater effort and get beyond just sitting around trying to render this in a dispassionate way. So I created this painting.

Arnold Blanch saw it first. Blanch thought it was very beautiful—and it is very beautiful—and he paid a lot of attention to it. He had other students looking at it. Then, in the afternoon, Kuniyoshi came in. He was a different personality from Blanch. His was a kind of prewar samurai persona: he didn’t say a great deal. One had to pay very close attention to whatever it was that was going on. He taught very much by example, by demeanor and bearing. He asked me to bring the painting into an adjacent empty studio. He closed the door, and we were in there, with the painting up on the easel, sitting in silence for at least twenty minutes. This was kind of a moment that we were living through. Then he said, If you keep painting that way, you’ll be dead by the time you are thirty. And he got up and left. I kept thinking, Well, this is important. I should be paying close attention to this and try to understand what he means because he is not going to explain it. He is leaving it up to me. That was very important because, after all, everything is left up to the artist working alone in their studio, regardless of whatever else may be going on. They have to somehow turn to themselves and figure it out.

I went back to where I was staying in Woodstock, which is where this happened, set the painting up, and tried to look at it through Kuniyoshi’s eyes. I kind of got it. That painting was a very complete painting. It was so complete that it answered all of the things that it had set out to answer and didn’t ask any questions at all. It was a dead end. There were no possibilities for a subsequent painting. This understanding has followed me all of my life. Paintings are no absolute answers to themselves or anything else. Whatever it is that they achieve, in the course of their creation, things come up that can’t be dealt with in a particular piece of work. One recognizes those things and puts them on hold until one gets to the next painting and drawing. But it is not six subsequent paintings painted into a single painting with the hope of getting to the end of everything. Working through these choices as an artist and being around artists who supported that kind of education is what the League made possible. In any case, that was a major moment.

Cassidy: You describe the Art Students League as allowing you to grow and to pursue these things freely, which I think echoed some early encouragement from your parents to pursue what you felt was interesting and valuable and to have a confidence in your own instincts. It’s a position contrary to being the good student and conforming to lessons or fundamentals that were offered in schools. It was an unusual attitude for parents to take with children at that time.

Dorfman: I think it was and continues to be very unusual. The idea of distinctiveness and the importance of personal choice, so long as it was creative and not destructive or harmful to someone else, was an important thing to be valued. My family said that I had the responsibility for saying something or doing something that would be a contribution and of value and importance. That was encouraging. They were both thoughtful, creative people. My mother was able to play the piano. My father was a painter himself by avocation, who worked as a creative art director and writer. A lot of my growing up was spent around art and artists. My father had studied with Kuniyoshi at the New School. I have a sister, artist Joan Busing, who spent a month or so working with Arnold Blanch before I got to him. There was an ongoing constructive validation and reassurance at all times, provided I took the responsibility for the doing of these things. In order to go to the League, I had to have a work permit for part-time work and to find an affordable place to stay. I loved all of it. I loved the League and everything about it. I really did.

Cassidy: Do you think those early affirmations of pursuing your own course, which were later reinforced by League instructors, helped you transition out of the classroom and into your own studio?

Dorfman: No question about it. It is important to note that I saw otherwise at the League as well, with two or three other instructors whom I worked with briefly. I found them drawing over my drawing and telling me that whether I was using red or not it should be on my palette. I understood what was happening well enough to respectfully decline and quietly leave the class and go someplace else where it was possible not to put red on the palette until you needed it. It was this idea of knowing both what is necessary to what is going on and what is going on right in front of you rather than accepting some other thing that was carried into the room that existed before you did.

Cassidy: It sounds like the opposite of curriculum or academic teaching method.

Dorfman: It is the opposite. I think the creative act is very different than the ability to perform a skill set. I think what needs to be understood are what one’s persistent preferences or choices are and then to be able to give expression to them in a constructive way. I think that individual choice is as distinctive as the human being who makes those choices. We are part of a collective, I understand that, but within that, there’s this other thing operating: the willingness to risk identity, come what may. That is essential to creation.

Cassidy: Let’s go back to the retrospective and the selection of the forty-three works because that can’t be a small task. You’re culling them from three different galleries and from your own storage. There’s a lot of work. What is the process of sifting, sorting, assessing? You’re working with a curator who might have his own agenda about what goes on the wall and different ideas about how to represent an evolution, a life, or themes and variations in the work. How did that process unfold?

Dorfman: There was, of course, the idea of wanting to exhibit work done over a span of time. But it also involved selecting out those works that would also hang well together. It is possible to have a very different kind of exhibition if it is approached chronologically—if one selects work just in terms of how many pieces there are from certain points in time. We didn’t do that. We picked out pieces that did reflect that whole timeframe that would all look good together. So, in terms of the period 1988 to 1995, there are maybe only a half a dozen pieces of work. As we get closer to the present time, there are more pieces of work in certain years than there are in others.

I had a few very friendly, cordial, and accessible people that I was working with. There were certain choices that were made that I didn’t agree with, and certain choices that I made that someone else may not have agreed with. But once again, in the end, they trusted me. I really tried my best to understand what they were doing and to try to accommodate their concerns. But I restored certain pieces to the exhibition that they were not planning to include.

Cassidy: Did you think that in the end they understood your choices? Were you able to make your case?

Dorfman: Very much so. Everybody was just great. There was one piece, Sijo (1989), which got in very late that I’d suggested early on. It was part of a series. The idea was to get this piece of work hanging high on the wall, so that when you came into the gallery and looked straight ahead, there was a group of very recent paintings, then large wall text with the show title. Above that, hanging next to heaven, was supposed to be this painting. I really it wanted it there. They did everything they could to find a way to get it there. They wanted to move a cherrypicker into the space and somehow get into the walls and find a way to suspend it. When I went to see the show for the first time, I noticed that it wasn’t up and asked about it. They explained that these things were becoming very problematic from a practical standpoint. The painting was in the building, but it wasn’t up. There wasn’t any more room. So I said, Isn’t there some way that we can get this into this exhibition? Once again, we found a way to accommodate each other’s concerns, which was nice. They did find an unusual place to hang it, and it did very well actually, even with less light. There was that kind of back and forth and a lot of reciprocity and mutual respect. Everybody has been just grand.

Cassidy: Can you tell me a few things that you learned visiting the exhibition that you didn’t know about yourself, the work, the process, what was going on at a particular point in time when you were fixated on something?

Dorfman: The very first thing was this sort of mundane and not mundane issue. With all the shows I’ve had over the years, I have always had some kind of a hand in deciding how things were going to be hung. The exhibition was laid out and planned, just before, tentatively, on paper, by myself and artist and League instructor Deborah Winiarski. I was allowed into the room during the process. But when the show was hung, I was not there. This would be a different kind of an exhibition, so I would simply trust a few other people to do it: Director Knauer, artist Vincent DiMattio, and Deborah Winiarski. So I had no idea what this exhibition would finally look like. When I walked in, I was stunned. I never could have arranged a show as well as they did. They were able to understand something that I would have gotten in the way of, no question. There are all sorts of ego issues and issues involving self. The show is beautifully hung, and I wasn’t there to have anything to do with it.

Cassidy: I’m wondering what you see on the walls now that the works have been assembled together. It would otherwise be impossible for you to see, at once, work from a thirty-year period. A retrospective affords a vantage point that you can’t normally access. These are works of scale; you need to be in their presence to really see them. What have you gained from walking into the gallery, at different points, and seeing people react to the work on the wall? The retrospective is almost three times the size of one of your regular shows. What do you glean that can help propel you to the next question in your painting? How do you understand yourself maybe a little differently than you did looking at the work? That’s a huge milestone in itself.

Dorfman: It struck me in a coherent way that creating those paintings, the doing of them, has been the great and loyal constant of my life. The works were all very close, more than great friends. There was also a sense of persistent concerns, persistent feelings, the persistent presence of qualities of feeling that I love. I have never seen my work that way. I had thought about that, but I was never really sure. I didn’t know that until I saw all these pieces together, at one time, regardless of size or materials. It is an amazing thing. I think a show of that size, with that many years involved, reveals what oneself is up to more than a more ordinary kind of exhibition—with due all respect to the others. I never had such an experience before. I found myself even saying to another artist at the time, I thought this is what I needed to see happen, and here it is. I feel vindicated—unless I’m deluding myself [laughs].

Cassidy: So it’s a good feeling and an affirmation.

Dorfman: Oh, it is a wonderful feeling. Yes, because you can be affirmed and validated and so on and so on and so on. But it comes in spurts and starts and stops. Then, here is a whole symphonic event going on that carries through an extended length of time. What a surprise, a very special kind of surprise.

Cassidy: Is it a catharsis, in a way? Or is it a catalyst to do more? Does it set a new agenda?

Dorfman: I think it is that, and it is cathartic also. One of the things that it has done is confirm something that I’ve suspected: one can trust one’s impulses. Walking out of that show for the first time, I was thinking the best thing to do now—or over the next one hundred years—is to move on with that. When something comes to mind, trust it. Go with it because it is doable, and you’ve just noticed that it is doable.

Cassidy: And it worked.

Dorfman: And in a way that you’ve never quite seen before. I suspected this was so. But now I’m reasonably confident that it is. It was cathartic in the sense that, since the first viewing, when I walk into my studio, I feel like everything is cooperating. It’s just amazing. Even when things get difficult, it is in a cooperative and necessary way. The act of creating things becomes much more pleasurable, which I would not have thought prior to seeing this. I have done two pieces of work since the opening. I was amazed that they came into being. You know, you want red, go ahead and use it because it’ll work. So just go there and trust it and everything will be OK.

Cassidy: I want to ask one last question about the retrospective’s periodization. The starting point of this show is 1988, which leaves a big gap between 1952, the year of your breakthrough painting Broken Pitchers, and 1988. Can you explain why 1988 was a good starting point for the show?

Dorfman: That’s a great question. There was a persistent issue that had been following me for many years. For those in-between years, there were concerns over whether or not I was going to fully and unquestioningly accept what I believed in or whether I was going to try to adjust to a more categorized way of thinking about things and find what I needed to do within that. Between 1960 and 1988, I attempted to rearrange or redefine what a painting space could be, and what painting meant or what it might mean. I became increasingly more conscious of the fact of painting not always resolving itself as just paint on a rectangle. It has only been relatively recently, since the early Renaissance, particularly in Europe, that painting was a portable board or a canvas with four right angles that you could lift and hang. Suddenly, there were collectors and people who were owning things and putting things in their homes, which was rarely the case prior to that time and didn’t really settle itself that way until the Reformation in northern Europe.

So I was struggling with that during that period, reordering what I did within a rectangular space but letting that space be the field for the work. I kept bringing other possibilities into my work throughout those years. There were oval canvases and circular canvases with wooden flanges. I have reproductions of them in early catalogues. When I was represented by Kennedy Galleries, they had a large exhibition of those pieces. I needed to feel within myself that I was stronger with what I was doing by either staying with four right angles and putting it all down with paint, or whether I should just go ahead and pay attention to just what was in front of me and follow what seemed to be necessary to that. When I moved from the one thing more fully into the other, people got used to it after a while.

There was a huge turning point that occurred around 1983, when I had a painting called Rain Field in one of the Art Students League’s windows. It was a composite of three sections. I was walking along 57th Street with Larry Berger, a very dear friend of mine, a painter, who had also studied at the League. We had just come up from my show at the New School, and as we passed the League, I asked him what he thought about my painting in the window: What do you think, Larry? Are we going into this now full blast, or what? What do you feel that constitutes my real strength as an artist? I’d already had like thirty-five shows. Larry said, Well, what do you think? I said, Well, honestly, deep down, I think it is the painting in the League window not the painting that is down at the New School. He turned to me and he said, Well, I’m glad you said it first. There’s no question about it. It’s the painting in the League window.

After that, there was no looking back. If a painting needed a piece of steel or a piece of wood, or a combination of this and that, along with all of the painting that goes on, it got it. There was no questioning of whether it was valid or not valid. It was a better piece of work. I always felt better about it. I felt it had a greater degree of integrity. It was more true to what it needed to be.

Cassidy: So you did have a moment of validation, of somebody saying, This is the work you should be pursuing.

Dorfman: I’d thought that was what was going on. But you spend so much time in isolation. You don’t know what you’re hearing or what you’re reading. Then, there have always been people who appear at different times who are just wonderful. They affirm or validate something that you may have been suspecting about your work.

Cassidy: So the moment of clarity for the artist can come when the work is received and validated by someone. It’s reinforcing.

Dorfman: I don’t depend on that, but it can be.

Cassidy: It helped you break through some last inhibitions about where you were going.

Dorfman: I think you’re right. It might have happened anyway, but it also might not have. I don’t know. I think it was important to hear what was being said, and to be able to somehow assess it and make sense out of it in some way that is useful to oneself and one’s work. Is what I’m hearing something that is strengthening? For me it’s always this question, Where are your greatest strengths now? Is there something that is being said to you or something that is being is written that will reinforce those strengths in some way? It is a sort of weeding out or filtering process.

Cassidy: It’s a nice place to be perched, for the time being anyway.

Dorfman: Oh, it’s wonderful. This exhibition really shows all of this. Every single one of those pieces I can remember what went on around them, what happened, what sort of crisis occurred in the middle of doing the thing. This show keeps affirming, again and again and again, something about choosing your strengths. For me, those need to be choices having to do with things that I love, not things that I don’t like.

Cassidy: I think it is sage advice and a value affirmed by the very atelier-based education that’s offered at the League.

Dorfman: Absolutely. The opportunity is there.

Bruce Dorfman: Past Present was on view at Monmouth University’s DiMattio Gallery from September 6 through December 18, 2016.