I’m sure my experiences as an aspiring artist, in some degree, are common to many. In 1969, after high school graduation, I was looking for a college to attend where I could attain a BFA as I furthered my art studies and training. I was sorely disappointed with what I encountered in the university system in the early 1970s. I felt that the system failed me in exactly what I needed and had been searching for: how to improve my drawing and painting. Academic subjects such as literature, psychology, and art history were fine. But in the studio courses, there was a total lack of direction. We were left on our own to do something “new” or “different.” There was no actual “point of view” taught regarding traditional or abstract art. In the figure drawing classes teachers talked only about outlines. There was no construction, proportion, or form. In short, students were not taught how to draw and paint.

Oil on canvas, 24 x 18 in.

My teachers subscribed to a hands-off approach. Instead of critiquing a drawing or painting and giving guidance about how to make it better or improve upon it, they would say, I don’t want to influence your creativity, or, You need a little bit more blue there, pointing to a model’s blouse. I would look at my palette where I had five different blues and turn to the instructor looking puzzled, asking, Which blue? How light? How dark? Should it be mixed with something else? No reply. In one drawing class, the model was simply dismissed for the entire semester.

I began to understand that the university system produced art instructors who could neither draw nor paint, and when they graduated, they stayed in the system to “teach” those coming in. In many institutions, this pattern persists today.

After college, I studied art independently. Then I read an article about Frank Mason in a 1974 issue of American Artist. The striking effects of light as well as the energy and vitality of his work attracted me. It also appealed to me that Frank ground his own paint and made his own varnishes and painting medium. I decided that the Art Students League was where I must go. The League represented everything I was looking for. The idea of studying with actual practicing artists was hugely appealing to me. I discovered a camaraderie and excitement among the students as we all learned together.

Frank Mason was the reason that compelled me to leave my small Pennsylvania town for New York City. He was the master I had been looking for. I spent five years painting with him in Studio 7 on the fourth floor and seven years studying landscape painting with him in Vermont. In my last two years of study, I became the monitor of his class.

At the League I painted hundreds of heads and figures from every angle, and I learned how the light reveals the form through space and atmosphere. Frank would say that most didn’t get the concept of atmosphere. He meant that too often the student copies the subject and will miss the subtle lost and found edges and the cool half-tones and turning planes. It’s about learning to see. These concepts were thrilling for me to hear, study, and understand.

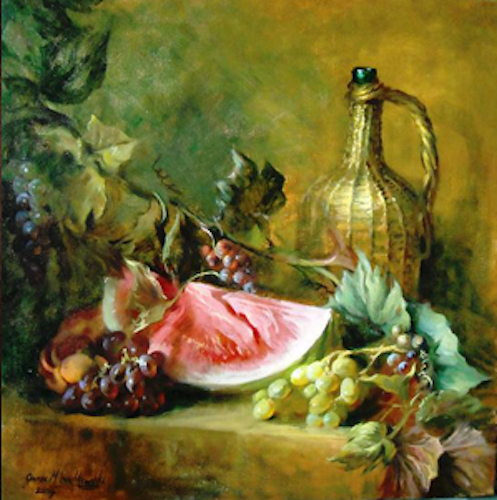

Oil on canvas, 20 x 20 in.

Mason would take my brush and show me what he was talking about—the master demonstrating to the student how the painting could be improved upon—a tradition dating back centuries. It was such a contrast to what I had encountered in the university.

Words only go so far. I learned by watching how to mix the paint, how much paint to put on the brush, how much medium to use, and how to apply the brush to the canvas. Mason stressed technique as well in painting. H discussed transparencies, opacities, underpainting, glazes, and the preparation of materials. These were subjects I had never heard about when I was attending the university.

Another of my instructors, Robert Beverly Hale, once said, “First we draw what we see, then we draw what we know, and then we see what we know.” This philosophy of teaching, which I encountered in Mason’s and Hale’s classes, stressed the big masses: getting hold of the big shapes, the movement of light and shadow on form. Mason also showed me how to think beyond the boundaries of a canvas. He said the composition began outside the canvas, went through it and out the other side. The artist had to create in paint the atmosphere and the air that the model breathed. What a grand way of thinking!

I learned color by painting the subject in front of me. The natural light revealed the proper value, shade, and intensity that was required.

Those years at the League taught me that style, like handwriting, is something a person is born with; it’s not acquired. Each artist’s work is unmistakable from day one. it is apparent when thirty people paint a portrait of the same subject: the painting is easily identified with the individual who painted it.

I’ve come full circle. I returned to teach in the university system that failed me as an aspiring artist.

The drawing classes of Robert Beverly Hale have been written about and talked about as legendary, and rightfully so. He was a one-of-a-kind teacher, bringing his artistic knowledge together with his philosophy, poetry, wit, and wisdom. He was brilliant at simplifying the complete anatomy of the human figure. From him, I learned that the more knowledge artists have, the freer they are to express themselves. In this inspiring atmosphere I became the artist I wanted to be.

More than thirty years after I left the university, I was asked to design a fine arts curriculum for Point Park University in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. The university knew of my work and told me the timing was right to introduce a fine arts curriculum. This was quite exciting since I could now return to academia and teach painting and drawing the way I had learned it at the League and have taught it over the years in workshops throughout the country.

This past spring, I introduced foundation courses on drawing and painting. It was a challenge to develop a sequence of study by semester, but I feel I accomplished that in a logical progression.

My students learn how to shade the basic shapes of an egg, sphere, subject, and cylinder. Next, they paint a composition using these shapes in a black and white still life. They subject may be, for example, some apples with a cylindrical jar. In this way, they study value relationships: form, light effect, and the concepts of space and atmosphere. Students continue with the basics of the color wheel: mixing complements and learning how to control the intensity of color. Then, they paint a still life in color with two or three simple objects once again.

After gaining a good understanding of shapes, forms, light and shade, and color, they paint a portrait. The progression of study moves from the simple to the complex. Hale would say that if you could draw an egg, you could understand how to draw a portrait; the features of the face are comprised of the basic shapes in one form or another. My students continue by learning about the planes and proportions of the head and its features. Next, they learn how to turn the ideal head into a portrait likeness. We finish the semester by studying the proportions of the skeleton of the human figure, touching on the musculature. I stress capturing the action in the figure’s pose just as Frank Mason taught me. Without first capturing the sweeping gesture, there is no point in developing the figure drawing further.

I feel this is as comprehensive a program as can be accomplished during a semester within a structured college atmosphere. Compared to the League’s schedule where a student has an entire week with the model, my class has twelve to fifteen weeks in a semester. So, students have four sessions a month to draw and paint. I also give them out-of-class assignments to work on, and I take them on a field trip to a Pittsburgh museum where they study a painting that relates to what we do in class. They write an essay about that painting: the period, the style, the artist, and so on. We touch lightly on art history. I believe it has substance and depth that the student can then use to pursue any direction of creative expression. In the coming year, I hope to introduce courses on artistic anatomy, portraiture, figure and landscape painting.

I’ve come full circle. I returned to teach in the university system that failed me as an aspiring artist. I now instruct students in the elements, concepts, and techniques of painting and drawing that I learned at the Art Students League.

The experience has been both rewarding and ironic.

This article was published in the Spring 2011 print issue of LINEA.