[1]

[1]At some point during my first year of study at the League, I became aware of the National Academy of Design art school, at the corner of Fifth Avenue and Eighty-Ninth Street. This was near where I was living, so I went inside to have a look and learned that Harvey Dinnerstein taught there. Harvey was not yet teaching at the League—he started here in 1980—but he was instructing at the Academy and the School of Visual Arts. I registered for his morning class at the NAD in 1979.

What most interested me about Harvey were his take on the world around him and his technical abilities. Other instructors of figurative painting were heavily invested in paraphrasing old masters, whereas Harvey, though deeply knowledgeable of academic precedent, was responsive to modern life. He’d covered the bus boycott in Montgomery and painted kids in bell bottoms. His work was humanistic and political. Harvey’s technique was constructed upon his draftsmanship; he possessed the assurance of someone who knew the craft. This was a significant qualification when I was looking for a teacher, in an era before figurative ateliers taught by technical marksmen proliferated like mushrooms. His mural, Parade, was a tour de force, but it was the prints of Harvey’s drawings that the Academy featured in its first floor offices that resonated.

[2]

[2]At any rate, I was in the right place. The natural light in the Academy’s studio was perfect, and the atmosphere in Harvey’s class was serious and engaged. It was also fun. There were a few students my age, including Nomi Silverman—Burt’s niece—which I took to be a good sign. After some false starts, I stretched larger canvases and began to thrive. Once divested of a newcomer’s reticence, I came to class with pronouncements re: masters who were over or underrated, and much to his credit, Harvey refrained from arguing or agreeing, allowing me to work through my own interpretations. I think he really enjoyed the enthusiasm of young students. His critical instincts were acute. Generally he gave me great leeway. One morning, stymied by the difficulty of mixing cool flesh tones, I asked what colors to use, and when Harvey answered “I don’t know,” the effect was liberating. (How welcome this was, while at least one well-known instructor sold a line of pigments with pre-mixed skin tones, thereby promising to streamline a student’s need to hash out the issue for him or herself). Another week, as I struggled with a canvas, I wondered if some poses were just inherently less interesting than others. “No,” Harvey answered simply, henceforth removing what had been a reliable fallback alibi when a painting started to go south. If these recollections sound terse, they’re leavened by other memories, like the time I gushed over a show of work by Thomas Anshutz, and Harvey accompanied me to Graham Gallery. He encouraged us to attend an exhibition by a young painter named Mary Beth McKenzie[3], and brought to class a photographic portfolio of work by another young painter I’d never heard of, Ron [4]Sherr. One morning, he introduced me to a fellow student, Steven [5]Assael, who drew in a small sketchbook with a ball point pen. Harvey wryly mentioned an older artist who preferred models with uneven breasts, surely the most interesting reference I’d heard to physiological asymmetry as an alternative to classical ideals. It was Harvey who encouraged me to see luminous color not only in light areas but in shadows as well, which is a useful observation for living as well as for painting. This advice had a permanent influence on my mode of seeing.

[6]

[6]Harvey strictly limited enrollment to the NA class—it was small, and I felt blessed to get in. After it opened I crashed his League class, which originally ran in the mezzanine studio and was full to the rafters, but I greatly preferred the relative quiet of the Academy environment. I can still hear him exclaim “Smashing!”, when he approved of a work in progress, one of his boot-clad feet tapping on the floor as he studied the canvas.

The occasion for these recollections is a show of Harvey’s paintings and pastels right now at Gerald Peters Gallery. My responses of nearly forty years ago are largely intact, and now more deeply appreciative. The exhibition is titled Harvey Dinnerstein’s New York, and it’s a view of the city that is by turns poetic, rhetorical and personal. Even when the works carry a rougher urban edge, pictorial grace takes precedence. In Blood on the Tracks, every shape is calibrated, the bright colors of a subway worker’s helmet and vest—the latter is a particularly well-drawn passage—played against a medley of grays. The shrouded figure in Homeless, also painted in profile, is so elegantly abstracted as to nearly transcend the harshness of the subject.

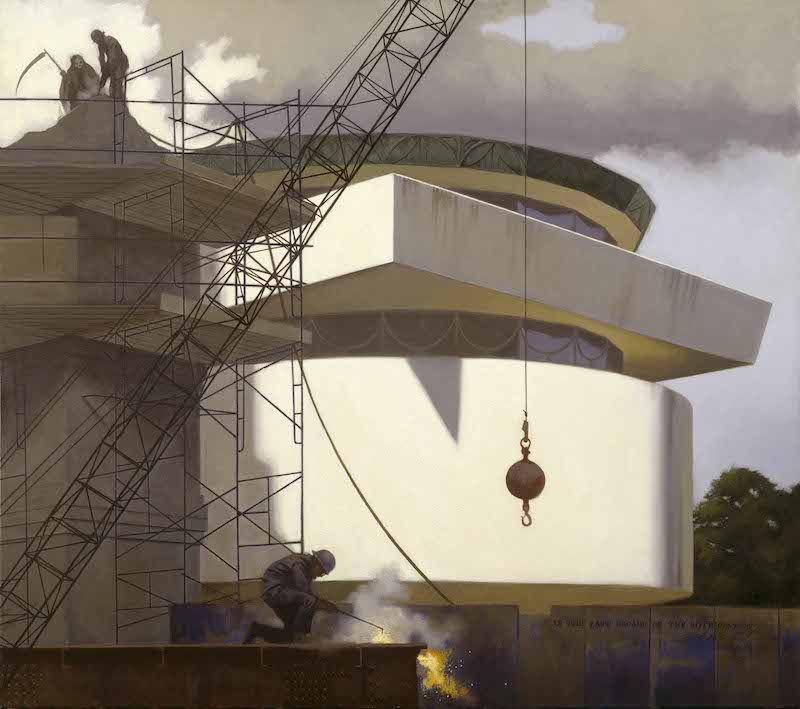

The large oils celebrate the city’s spaces and its denizens. People are arranged as actors on a stage; even Harvey’s intensely studied portraits exist in a broader rhetorical realm. His figures are framed and often dominated by the hard lines and ornamental filigrees of architecture. Triumph of Time, with its bit-playing ironworkers laboring around the Guggenheim, has grown on me since I first saw it more than two decades ago. The museum, a block south of the Academy, is not the sort of structure that Harvey usually delights in painting, and the focus on its fragile concrete bulk alludes to the transience of contemporary art. Allowing the sterile slabs of the museum’s facade to dominate the composition was an audacious move; the red ball suspended like a pendulum from the crane is a perfect shadow tone, weighted and luminous.

[7]

[7]Many of the big canvases are set in parks, and all of them bespeak a fascination with the geometry and textural substance of arches. Since the early 1980s, Harvey has made dozens of drawings and paintings of the arches and tunnels in Prospect Park, the mood gradually shifting from bucolic to elegiac. His work has gotten starker and stronger. In Life Cycle, Harvey paints himself painting next to a mostly shadowed arch. People of various ages are silhouetted within the tunneled path against an autumn landscape. In Passage in Winter, two figures are seen again walking through the tunnel beneath an arch, this time close to one another and silhouetted against snow; the figures are the artist and his wife. Small and distant, they reside in an allegorical space. This is less so in recent pastels where Harvey and Lois take their places in the foreground, especially Old Couple, a tender view of the couple in black winter garb, seated together on the subway. Of themselves, these double portraits comprise an extraordinary and subtle suite of poetry on aging together.

On occasion I bump into Harvey at the League, or more rarely meet for lunch. Now almost ninety, he is still both generous and skeptical. Brilliant in conversation, he is one of the best listeners I’ve known. It surprises and gladdens me that an artist who possesses such a sharp eye, with so little patience for bullshit, exercises a consistently lyrical vision in his art. Go see his large pastel of the Central Park fountain, Bethesda, in the current show; angular, elliptical, dark and light, it is, in the end, a romantic view of the city. It is Harvey Dinnerstein’s New York.

Harvey Dinnerstein’s New York continues at the Gerald Peters Gallery[8] through March 16, 2018.

- [Image]: https://asllinea.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/Dinnerstein_Bethesda-copy.jpg

- [Image]: https://asllinea.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/Dinnerstein_Passage-in-Winter-copy.jpg

- Mary Beth McKenzie: http://www.marybethmckenzie.com/

- Ron : http://ronaldsherr.com/

- Steven : https://steven-assael-mr8x.squarespace.com/

- [Image]: https://asllinea.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/Dinnerstein_Triumph-of-Time-copy.jpg

- [Image]: https://asllinea.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/Dinnerstein_Old-Couple-copy.jpg

- Gerald Peters Gallery: https://www.gpgallery.com/ny/exhibitions