Suzanne Benton is a printmaker, sculptor, and performance artist. Based in Connecticut, she has travelled to more than thirty countries to share her art and her unique mask-tale technique. She is represented in museums and private collections worldwide, and has exhibited in over 150 solo shows. The author of The Art of Welded Sculpture, as well as numerous articles, Suzanne is listed in Who’s Who in America, Who’s Who in American Art, and Feminists Who Changed America. More information about her work is available on her website.

Your art is deeply entwined with your feminist activism. Can you describe the way that these two entities support each other?

Feminist precepts and my involvement in the Second Wave movement greatly expanded my life and my art. Heady gatherings in the 1970s of Second Wave NYC and CT feminist writers, poets, artists, dancers, and actors propelled me (formerly a painter and by then a metal sculptor) to create welded steel and bronze masks. My masks became a vehicle for my voice, our voice, and the voices of women worldwide held back by repressive legal systems and cultural conventions. I went on to create masks throughout the world and use them in workshops with women, children, and men in thirty countries. Knowing that listening and witnessing can heal—that many truthful tales deserved a further telling—I understood my role as a mask-making/performing artist was to gather and develop Journey Tales and perform them from country to country.

Growing up in New York City, I studied life drawing at the Art Students League and majored in art at Queens College, CUNY where the required two years of Liberal Arts grounded me in history, literature, philosophy, science, art, and music. I taught art at JHS 166, Brooklyn, for two years and was a practicing painter for eight years before studying welded sculpture at Silvermine and starting my life as a sculptor. I authored The Art of Welded Sculpture (Van Nostrand Reinhold, 1975).

Mask making and mask-performance carried me on my first worldwide journey in 1976–1977. I sought tales of women’s empowerment, but largely found tales of tragedy that mapped the struggles women faced in every country, struggles that crimped everyone’s lives. This work was more than a witnessing: it was a speak-out, a making known the hidden and ignored truths.

Masking was my guide and the open door. With techniques honed along the way, I led others into sharing long-held repressed life stories and awakened their feminist consciousness. I witnessed watersheds of feeling evolve into empowering visions of transformation. I listened and learned; carrying and retelling their mask tales in my travels and at home in the States. It was painful to face these difficult truths, and also exhilarating to see the work inspire others. It was truly a planting of seeds for change.

I also sought out aspects of culture that transcend the bitter realities. This opened me to worlds of wonder and infinite complexity, the shadow puppets, traditional mask dance dramas, Kabuki and Noh, gamelan and sitar music, glorious artworks unique to each land and crafted over centuries, temples of majesty and grace; all this is merely a fraction of the ocean of newness that engulfed me. Awakened to this experiential infusion, the simple noting of the play of light and color so unique in each land, the rising and setting suns, tapestries of birds and plants, the intricate fabrics and vibrant wares, if that were all, but no, it was being present in that light that educated me beyond my years of art training and devotion.

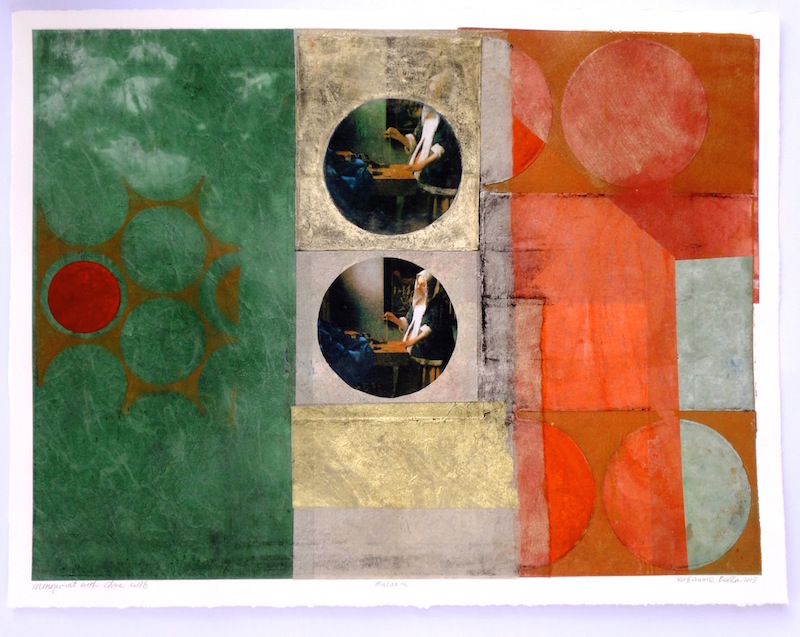

With this as background, it cannot be a surprise that by 1982 I was creating monoprints that intertwined images of Eastern and Western artworks within a many-layered abstract network of shape and color. The intention here is always to bring the past into the present, to honor, transform and enliven each sphere.

With my sculptured metal masks, I’d work with sheets of metal. Their weight sits well with the starkness of the dark tales that came from the sharing. In printmaking I use thin sheets of painted Chine collé (Chinese paper collage) paper. These sheets, which I paint in ways that reflect the subtleties of color I’d absorbed over time, have a lightness and delicacy that shows the medium’s influence on the message.

Before I entered the world of the mask, darkness was not unknown to me. My early years as a painter saw me through the loss of my second child to a fatal disease. Joy returned with the birth of daughter Janet in 1963, the year Betty Friedan’s groundbreaking book, The Feminine Mystique, caught America by surprise. Moved by its precepts, I signed on as a feminist when the National Organization for Women was founded in 1966.

I was drawn to masking for its power to erase the bias of being dismissed, to capture and command attention, and to empower the mask bearer to vital truth telling. Knowing my masks needed a voice, I began mask performances in 1972. My first mask tale, the biblical Sarah and Hagar was developed with Judith Hannah Weiss, a Theatre Studies student at Sarah Lawrence College. We performed that year at the opening of my mask exhibition at the Museum of the Performing Arts at Lincoln Center. That performance began my traveling life as a solo performer. Mask tales of Women of Myth and Heritage tales, and mask/story workshops found venues with feminist groups, churchwomen, and college students throughout America who were looking for the new voices of feminism.

In June, 1975, at Artpark in Lewiston, New York, I was creating large sculpture works in the midst of visitors to the park. I enjoyed working in the presence of people and imagined traveling the world, working among people as a feminist mask artist. That very summer I was invited to perform Sarah & Hagar and lead mask/story workshops for a mix of women of all ages and backgrounds at the United Methodist Women’s Quadrennial Conference, Norman, Oklahoma. My success at that conference led to the United Methodist Women’s and World Divisions sponsoring my 1976–1977 around-the-world tour. Their mentorship and support set the pattern that changed my life. With welded masks leading the way, I crossed cultural boundaries into worlds that opened my heart and mind.

In your artist statement, you say that the purpose of art is to explore humanity. Is teaching art processes something of a two-way street for you?

Part of the teaching process is being a listener. That’s how to discern the best ways to move forward with students. In my masking and printmaking workshops, I read a section What-Is-My-Way in Jon Kabat-Zinn’s book, Wherever You Go, There You Are. It’s a guide to meditation in beautiful accord with the creative process. I use soundings to attune the group and set a tone of acceptance for each person’s path. In setting the pace, I remind myself.

Though transplanted to Connecticut as an adult, growing up in New York City nurtured a sense of universality. The city’s subway, streets, schools, and neighborhoods point to the mix of people. My young ears and eyes witnessed tales of love and loss (and the Holocaust) told to my mother. Museums became my teenage haunts. The Met and MoMA (then with free admission) gave access to the global inheritance of timeless art. This glimpse of the wide world’s treasures had me longing to travel and discover the roots.

My worldview has developed out of the masking work that offers a window into the depth of lives otherwise hidden from view. The power of the mask allows the exchange of the honesty of our lives. It conveys the gravity of profound and oftentimes intractable issues, and of life stories sometimes too tragic to repeat, and it lets us share the stories that honor that which sustains hope and celebrates the joys that exalt our lives. This vital source teaches me the humanity to help myself and others explore.

How do the stories and methods you have accrued in your travels alter what you share in your work and how you convey it?

Welding sculpture initially found me working with the figure, and figures inside of figures, before entering the mask. The first stories were women of the bible. World travel expanded my reach into each country’s history (and herstory), mythology, and the emblematically personal stories revealed in workshops.

Going forward is both anticipatory and mysterious. There’s often a surprising shift. For example, I went to Köln, (West) Germany in 1982 not expecting to return that January and establish a studio to create twenty-seven masks on the theme of the Holocaust. I performed the Holocaust Tales in Köln, London, and in the U.S.A. before the films Shoah and Shindler’s List entered mainstream American thought.

Concurrent with working on the difficult theme of the Holocaust, I made collages that soon morphed into monoprints with collage techniques. I have since included printmaking in my travels, along with the mask work. My aim is always to respond to and respect the cultures wherever I am working and let the experience of being there enter the work. Where I am influences what I’ll do. The U.S. government sent me to many countries; I received a Fulbright to India (1992–1993), and other invitations and residencies. It seems a complex web, yet the work flows on. I shift from country to country, and so does my consciousness. It is as if I’ve never created anything before entering each different world, as though I am starting anew. Perhaps I am. That’s the elixir that draws me on.

In Bangladesh and India in 2011, I led a welding workshop at Dhaka University and created two masks, and a mask tale based on a current news story. I made paintings during an artist residency at Sanskriti that were then exhibited at American House, Delhi. In 2012, I worked on paintings at artist residencies in Israel and Spain in 2012.

My current project From Paintings in Proust began in 2013 and has carried me to Paris to see the paintings referenced in Proust’s great novel, Remembrances of Lost Time. I then went to Rome and to an artist residency in Assisi to explore Giotto (one of 200+ artists mentioned by Proust).

Last year, a journey to London, Prague, and Berlin took me in search of more of Proust’s referred-to paintings. Artworks have grown out of this new seeing. Printmaking has become a major vehicle allied to painting. The Monet Gardens in Giverny, France, led to an explosion of work, and now I’m feeling a thirst for more color.

I’ve taught a Printmaking Without a Press workshop at the Art Students League for the past four years, and lead workshops in Printmaking with Collage Techniques and Large Prints From a Small Press in Connecticut and Florida.

In performance, it’s the timing, the space between words and gestures, the chosen emphasis, the use of voice and movement. These elements have matured over time not only from practice, but from the reactions and interactions of work-shoppers, be they ragpickers’ children in Kolkata; India and Korea’s famous actors; notable psychiatrists; dancers; writers; and poets. Seeing traditional mask performances in Japan, Korea, India, Bali, Nigeria and Tanzania, and the Carnival celebrants in Kôln have had their impact. The pacing and rhythm are so crucial on stage are also building blocks in the creation of art.

You’ve been working with transcultural myths and media for a number of years. What changes have you noticed in the way that your works are perceived?

We’re lucky when the radical ideas of our youth become absorbed into our culture. It was shocking in 1972 to tell mask tales from a woman’s point of view. Nevertheless, audiences were receptive. It was the cause of the day. Some people would think I was the character I conveyed through the mask. Conversely, while working with women being trained as ombudsmen in Nepal in 1993, I was told that if the performing women didn’t wear a mask, people would think they had AIDS, or that they were the prostitute they’d been depicting in order to educate and save others from such dangers.

I returned to America after my first world trip 1976–77, and audiences still wanted mask tales of women in the Bible. There was little interest in other countries or the common threads universally depicting the struggles of women. That has changed. We have evolved as a country in terms of consciousness. What I’d been doing had been challenging, threatening and shocking. I didn’t care. I had to continue. A force from within drove me.

You use a number of media to convey stories through your art. What determines your choice for a particular project?

It’s all stepping-stones. I began as a painter while abstract expressionism was the mode of the day. That style was promoted as an expression of the artist’s soul. Though that ideal spoke to me, but realistic and surrealistic figures entered my work and became the expressive vein throughout my early years. Still honoring the face and figure, my 2005 retrospective at Queens College was titled Face and Figure.

Many series of masks have drawn upon the cultures that I explored through travel and my study of mythology, psychology, archeology, and history. After completing a series of masks from plays of Shakespeare for a winter term project at Oberlin College, I went to Kôln, to create masks and tales on the Holocaust. Taking on that darkness resulted in the monoprints I’ve since been making that capture a sense of beauty I likely absorbed in East and South Asia.

Do I know what I’ll create next? I take heart from Matisse saying that if you don’t know where you’re going, you’re on to something. I like the quote by Albert Pinkham Ryder about “moving out beyond the space where I have no footing.” I’d thought creating masks would be artistic suicide. I created over 700 with just 50 left unsold. These are my performing and workshop masks and in many ways the most choice. Mask tale performances and workshops brought me into worlds I’d never imagined. Who’d have known?

Moving on, step by step, somehow a path opens. It’s up to each of us to take the next step. It’s a huge adventure to be a traveling woman artist and receive accolades in many lands. The journey encourages me to take the risk and not falter. Joseph Campbell, whose work on the archetype has influenced my own, famously said to “follow your bliss.” My credo: be open to new possibilities, and seek the vein that brings out a new body of work. I’ve seen my work make others’ eyes shine. Passing the torch of inspiration is and has been my greatest joy.

The League holds a number of weekend, evening, and week-long workshops, in which League instructors and prominent visiting artists work with intimate groups of about a dozen students. Workshops focus on a particular aspect of art-making or specific medium or techniques. Suzanne has taught multiple League workshops in “Printmaking Without a Press,” in which students experiment with inking, line, stencil, and chine-collé, in order to produce their own prints without a press. A current schedule of upcoming workshops can be found here.

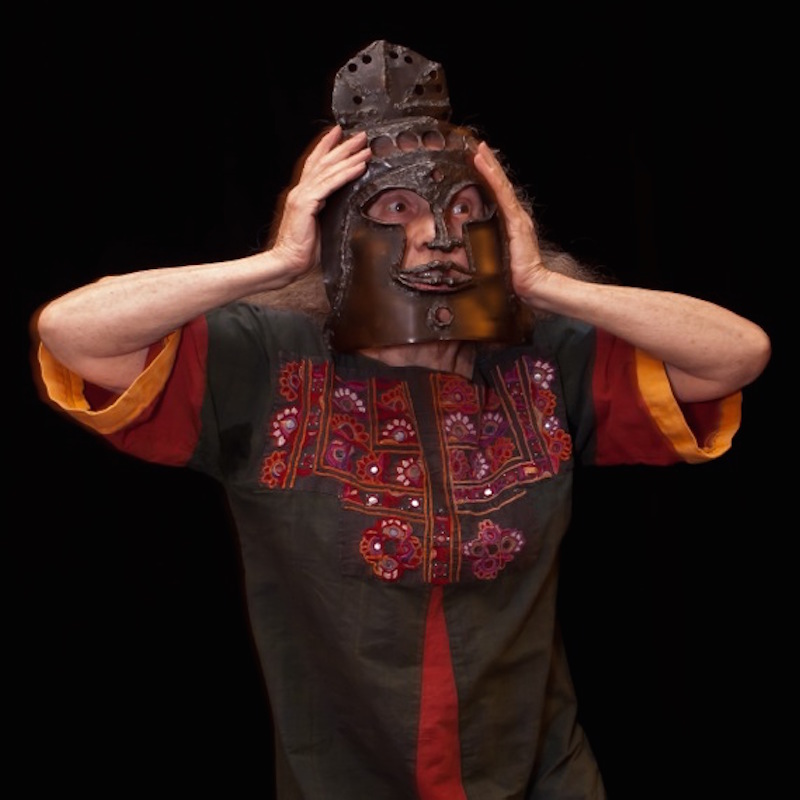

Chitrangada, an Indian Princess from the most ancient Indian epic, The Mahabarata. Mask (welded steel, 13.75 x 8.5 x 4 inches) and “Tale” by Suzanne Benton.

Job’s Wife. Mask. Welded steel, 11½ x 9 x 3 in. and “Tale” by Suzanne Benton.

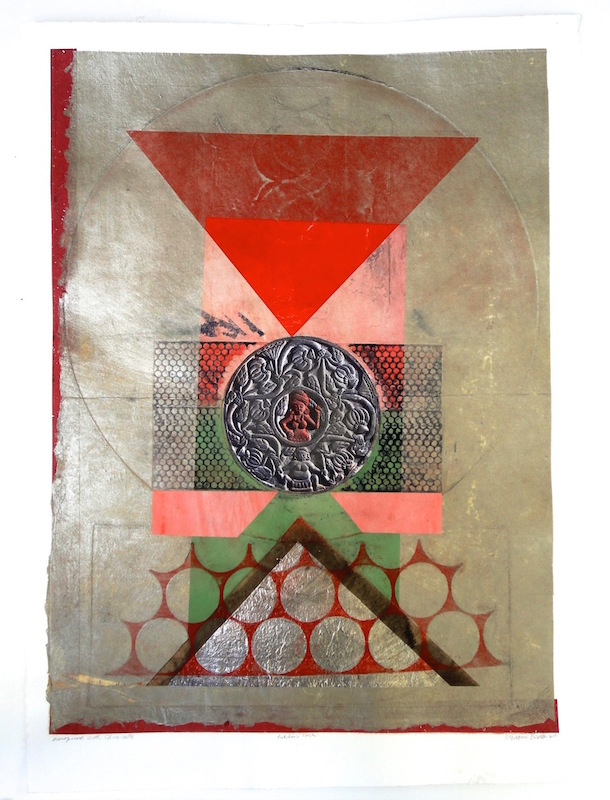

Suzanne Benton, Lakshmi’s Circle. Monoprint with chine collé, 27 x 20 in. Goddess of Good Fortune, Consort of Vishnu

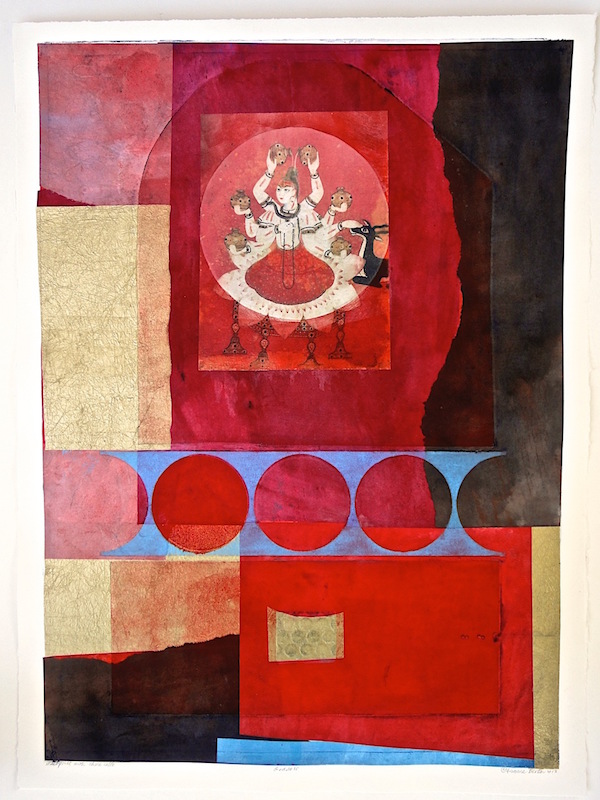

Suzanne Benton, Goddess. Monoprint with chine collé, 27¼ x 19¾ in.

Suzanne Benton, Bindi. Monoprint with chine collé, 10 x 7⅞ in. From the “Paintings in Proust” series with floral photo by the artist from the Monet Gardens, Giverny, France

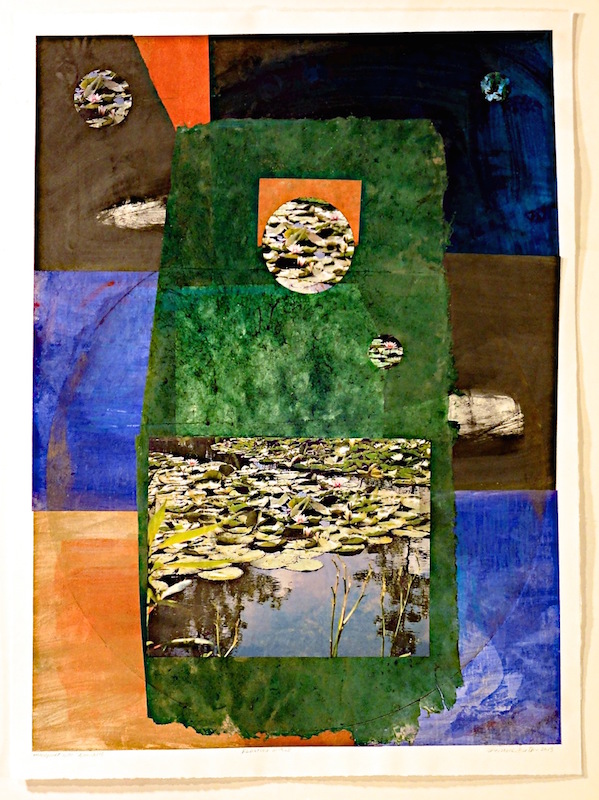

Suzanne Benton, Floating World, Monoprint with chine collé, 27 x 19¾ in. From “Paintings in Proust” series with floral photo by the artist from the Monet Gardens, Giverny, France

Suzanne Benton, The Hand. Monoprint with chine collé, 27½ x 19¾ in. From the “Paintings in Proust” series with detail photo of hand taken by the artist from Portrait of a Venetian Lady by Veronese, Louvre, Paris