To walk in the galleries of Africa, the Pacific Islands, and the Americas of the Michael C. Rockefeller Memorial Collection at the Metropolitan Museum of Art is to travel through a space-time continuum; a cosmology packed with objects of timeless dimension that exist in simultaneity. It’s beyond a stretch of the imagination. European explorers began their discovery of this art during the Renaissance. Much later, the twentieth-century anthropologists Margaret Mead and Claude Lévi-Strauss, among others, observed in their travels ingenious artistry among indigenous inhabitants of these rediscovered lands across the seas. Masks, totems, ornaments, idols, tools, and other ethnological finds from these continents now grace museums in the Western Hemisphere and can be experienced in less mysterious and exotic ways at close range and in climate-controlled rooms. Celebratory or utilitarian, ritualistic or shamanistic, they record sacred history and offer a path to the spirit world.

If one is to find inspiration, this is the place. It is magical and has become an important spot for me to mull over things and to formulate ideas regarding art, culture, and politics. My own art is an aggregate of memory and experience not limited to one accepted form, but rather informed by myriad data: prehistoric art from all corners of the planet; belief systems; science; bark paintings; mosaics and icons; found objects, and topical aspects of today’s globalized world.

Many art forms from these continents and islands remain under the radar, though if a recent uptick in auction sales is any indication, interest is widening. I root for the underdogs: bark paintings, sand art, totems, body art, and the dwelling ornaments from these regions. They always fascinate for their texture, color, and mystery. Images of humans and animals are reduced to geometric shapes and decorated with linear motifs including scarification marks. Outside of this sphere, they have become au courant—appropriated in fashion by contemporary urban and countercultural groups both to express their identity and to connect with their roots. The pictorial composition complements the minimalistic sculpture African Animal Object (Boli) found in the adjacent Main Africa Gallery. It is one of the crusty objects made with mixture of plant matter, blood, and ritualistic minerals as well as other dried out remains from previous offerings to renew spiritual powers. The spiritual power of a society is believed to reside in the Boli.

In the same area of the Metropolitan is a work by the Nigeria-based artist El Anatsui. Born in Ghana in 1944, El Anatsui has maintained an illustrious career for decades, most recently receiving the Golden Lion for Lifetime Achievement at the 56th Venice Biennale. His Between Heaven and Earth is a fabric-like installation loosely based on the traditional Kente strip-woven textiles of his native Ghana. The piece evokes movement, texture, and scale. El Anatsui recycled bottle caps, wire, and thousands of flattened tins and transformed them into a shimmering golden color that befits a regal crown. His vision and socioeconomic initiatives on behalf of his village are proof that art can serve as more than a catalyst and effect real change in society. The juxtaposition of El Anatsui’s contemporary work with ancestral objects makes him an unofficial ambassador of the old and the new, the traditional and the contemporary, in African art.

But there are other areas of the museum that, for me, hold an equally powerful allure, each for a different reason.

Byzantine art can be thought of as the oldest organized surveillance system, devised by an institution that very well understood power and control. The hauntingly hypnotic, iconic eyes in many paintings of the period monitored movement by the laity, in essence, putting them in their places. Medieval images told stories and parables that instructed the illiterate masses. Sinners were admonished to repent and obey the commandments in awe and fear. Illustrated by the diptych tableaus, triptych altar pieces, tesserae and frescoes, they left an indelible mark on the faithful. By and large, we appreciate the aesthetics, the mystery, the exquisite craft, and certainly the value of the objects, but beauty belies the dark side of faith, which, to some, is blind.

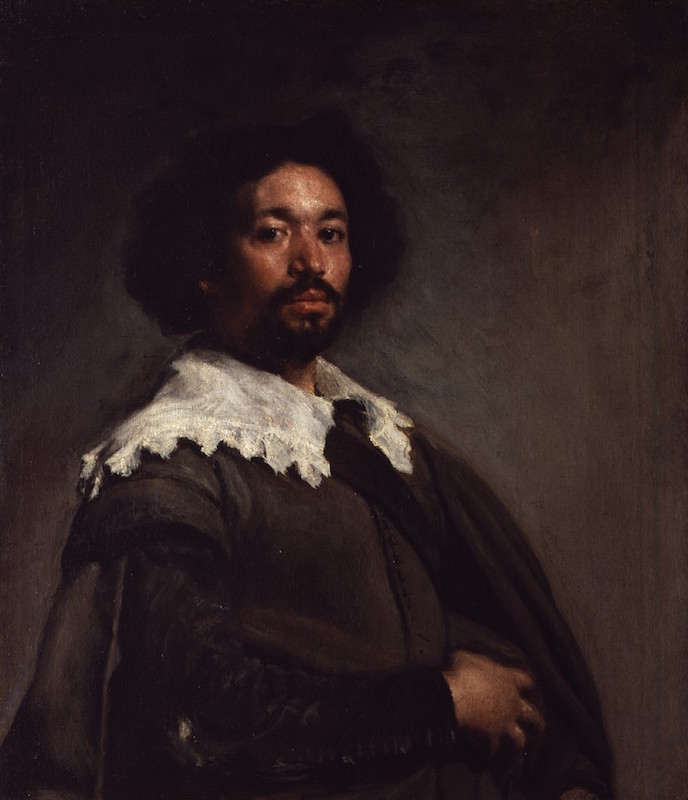

There were only two patrons of the arts during the Renaissance: the King and the Pope. Diego Velázquez painted the monarchy, while the era’s other famous Spanish artist, Bartolomé Esteban Murillo, painted religious themes. Velázquez’s dramatic lighting and masterful brushstrokes are two of the influences I had as a young art student of figurative painting and drawing. Velázquez oils deftly exude luminous glaze and auratic chiaroscuro that can magically transfix the viewer. Although his main assignation was to paint the royalty, Velázquez’s portrait of Juan de Pareja (1650), his assistant painter and, later, a freed slave of Moorish descent, is a standout. Another painting that is hardly royal, The Supper at Emmaus, delivers the religious experience of two men seated at a table with Jesus, who, as he breaks bread and shares it with them, recognize him. What worked best for Velázquez was the irony of his brushstrokes: the way he nailed characteristic flaws, human frailties, and the subtle facial tics of his royal sitters.

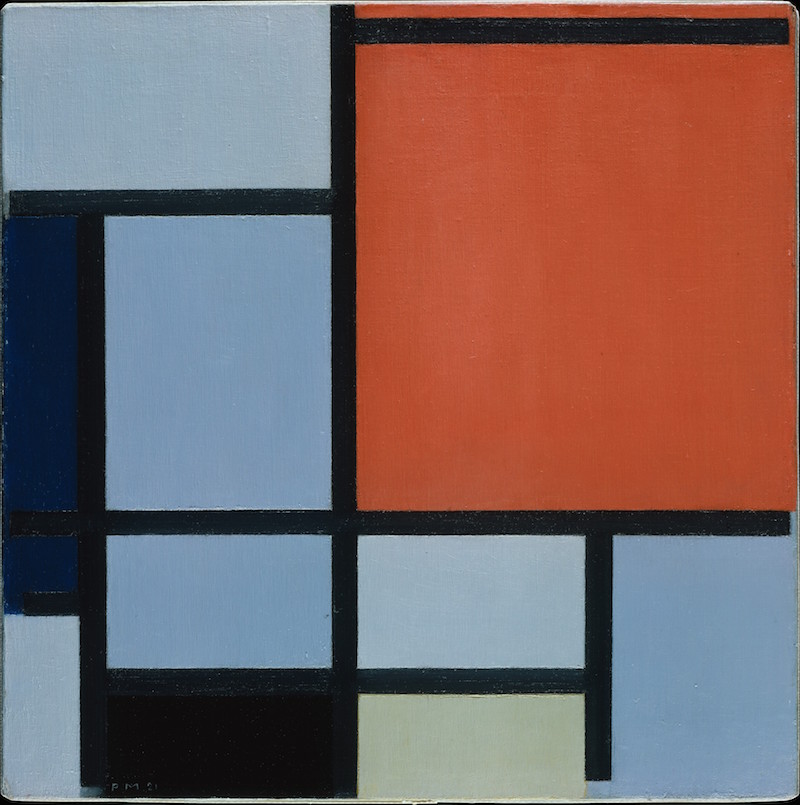

Finally, I could not leave the museum without stopping by the abstract galleries. I still look at Piet Mondrian’s small painting Composition (1921) for its remarkable freshness after nearly a century of existence. The work shows his signature neoplastic style in light blue, red, and yellow colors, bordered by horizontal and vertical black grids. It is Mondrian’s pure and ideal form of abstraction to rid painting of references to nature and any recognizable figure, focusing only on compositional elements of color, pattern, and planar relationships. Neoplasticism, which means “new image,” is derived in part from suprematism, a Russian movement led by Kazimir Malevich, who influenced nonobjective artists. Both Mondrian and Malevich asserted in their work a utopian vision to reorder the world and free it from history and literary narratives, which, in turn, changed the face of the twentieth-century art, design, and architecture. Mondrian’s later paintings, created in the 1940s, progressed to pure colors buzzing with high energy, rhythmic intensity, and upbeat tempo. Modernism in America went into overdrive in the direction of radical change. Other contemporaneous vanguard “isms” were De Stijl, introduced by another Dutchman, Theo Van Doesburg, and constructivism, which developed in Russia during the 1920s. We now associate Mondrian more with his popular Broadway Boogie Woogie (1942–43), which he created in New York, than most of his prewar European canvases.

For me the Metropolitan Museum embodies a cross-pollination of cultures in symbiosis. Like a vessel, it holds together the remnants of many civilizations. My selections are a testament to a shared commonality, artistry, human inventiveness, resourcefulness, and what we can do to uphold dignity by embracing differences despite our cultural biases.

Mariano Del Rosario teaches at the Art Students League.